Is there a “natural resources curse” as economists call it? This burning question arises in all resource-rich countries where the majority of the population is living in poverty. Political instability, conflicts, or poorly run institutions are all country-level explanations. But is it enough? Another important aspect of the question is that resources can be extracted in an artisanal or industrial way. The effects on local populations then differ widely.

In a recent article, we explored the case of Burkina Faso. In five years, this West African country has become the fourth largest gold exporter in Africa. The surge in gold production was triggered by the strong growth of the gold price during the 2000s, which resulted in the creation of eight industrial mines between 2007 and 2014. The number of artisanal mines increased from 200 in 2003 to more than 700 in 2014. Despite this, 43% of the population was living below the poverty line in 2014.

Artisanal mines have a bad reputation. Extraction using traditional and labour-intensive techniques leads to serious health risks and environmental damage. The economic benefits are also assumed to be low because of their comparatively low yields compared to industrial mines.

However, these artisanal mines are central to the livelihood of more than 100 million people in the world today. In 2014, in Burkina Faso alone, 640,800 people worked in the extractive sector, or 3.6% of the country’s population. Virtually all of these people worked in artisanal mines (industrial mines employed around 6,000 people in 2014). Paradoxically, studies quantitatively measuring the effects of artisanal mines are extremely limited.

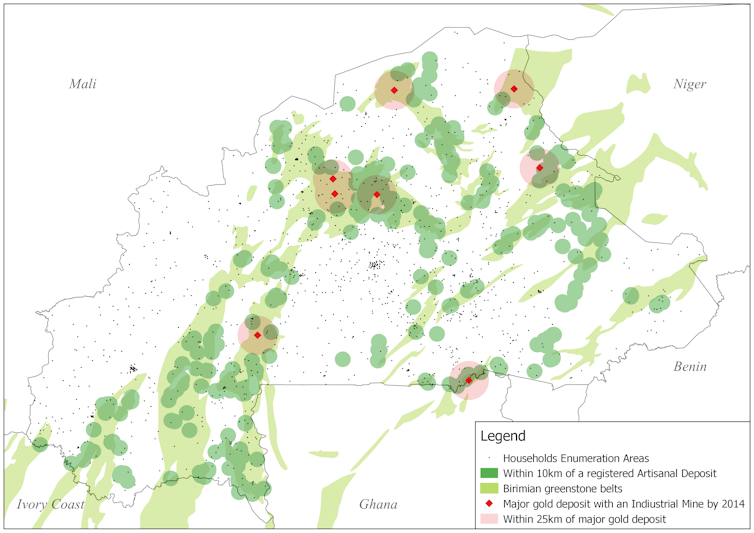

To try to understand the reality of the “natural resource curse” around artisanal and industrial mines, we compare in the article the standard of living of households living in the immediate vicinity of mines with the situation of those living further, before and after the mining boom. We look at household consumption, which is the best indicator of their economic resources in the absence of reliable income data. We benefit from geocoded data on surveyed households, industrial mines, declared artisanal mines, and geological zones of formation of Birimian green rocks, which constitute the main geological formation explaining the development of gold in Burkina Faso (see figure 1).

Artisanal gold miners stimulate the local economy

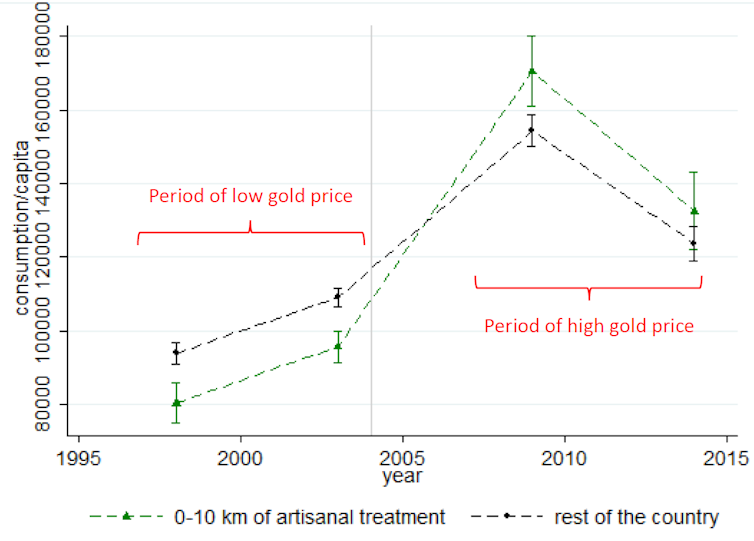

Our results indicate that artisanal mines have a strong positive effect on the standard of living of local populations. A 1% increase in the price of gold raises household consumption by 0.15%. During the gold price boom (2009 and 2014), these households consumed 10% more than households not living in close proximity to mines. Figure 2 summarizes these effects by comparing household consumption before and after the gold price explosion.

Households benefiting from artisanal mines have two types of activities. Either they are households likely to diversify their economic activity, or they are households that benefit from a stronger local demand for goods and services because of the activity of gold miners. We show, for example, that households working in the public sector do not see their income changed by the gold price explosion, while the effects are strong for those working in agriculture, services and trade.

Artisanal gold mining also appears to complement and not substitute for agricultural activities, even when the price of gold is high. Artisanal mining is indeed a seasonal activity, mainly taking place in winter, when the work in the fields is limited.

“Enclave” activities

During the same 2007 to 2014 period, eight industrial gold mines opened. The volume of gold that has since been extracted largely exceeds that extracted in the artisanal mines. The production techniques used differ widely. Industrial mines are capital intensive but provide high wages to their few employees and may trigger increases in local demand. We compare the level of consumption of households living near industrial mines before and after the opening of these mines, compared to other households.

We do not observe any significant differences in consumption trajectories between households living within 25 kilometres of industrial mines and other households (see Figure 3). We thus observe no effect of industrial mines on the standard of living of local populations. This result is consistent with the work of Alfred Hirschman, who describes extractive activities as “enclave” activities with little effect on local development.

This does not, of course, prevent industrial mines from having other effects, particularly at the macroeconomic level be it through exports or state budget. According to the Ministry of Mines, mining export revenues are valued at CFAF 1,022 billion in 2016 (1.56 billion euros), and industrial mines have also contributed up to CFAF 190 billion (290 million euros) to the state budget.

Rethinking mining policies

While we do not find any effects related to the opening and expansion of industrial mines, we find a significant impact related to the rise of artisanal mines in Burkina Faso, which has resulted in an income increase of 5 cents in euros per day for households living close to them (for an average income of 50 cents in euros per day, i.e., a 10% increase). Our results therefore call for a better consideration of the importance of artisanal mines for local populations in mining policies.

Such policies could, for example, seek to best ensure the cohabitation of artisanal and industrial mines, which often target overlapping areas. This could maximize the benefits from mineral resources, both for the central state and local populations. Finally, there is the question of local investments made by industrial mines. Despite a policy of social responsibility displayed by most investors, these do not seem to have a systematic effect on the local standard of living.