Does a walk in the park during your lunch break make you feel relaxed? Does lush greenery or a glint of sunlight on running water catch your eye and allow you to stare and rest your brain?

We recently turned our attention to these questions when we asked park users in the City of Melbourne to view films of walks.

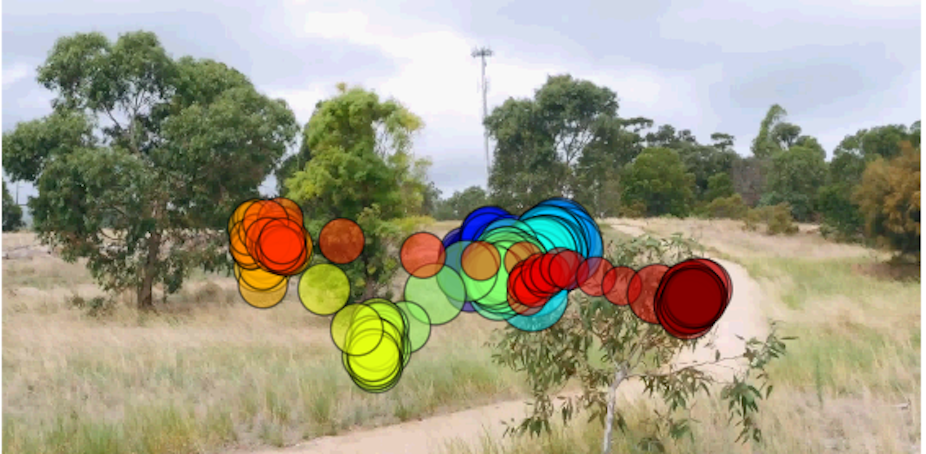

We used eye tracking – a technology that allows us to look deeply into exactly what you are looking at or paying attention to. Eye trackers follow your gaze as you look naturally around a scene. We see where your eye dwells and what things you skip over.

Where you stop is called a fixation and where the eye darts around is called a saccade. During saccades the eye is effectively blind. Watching what you stop to pay attention to and what you “don’t see” can tell us a lot about what might be going on inside your mind – what is driving your eyes to move about the way they do.

What you see can affect where you go, what you buy and how prone you are to accidents.

In addition, park designs have been shaped by a number of theories.

Attention Restoration Theory, for example, predicts that natural scenes promote fixations, and these allow the brain to recover from extended periods of concentration. This explains why parks are relaxing.

Prospect Refuge Theory predicts that we feel safer when we have a clear view of a scene and so can identify potential dangers. This explains why people take certain paths and not others.

Putting theories to the test

Eye tracking can test these theories. In our study, 35 respondents were shown four short films of walks through Melbourne parks such as the one in this video.

Respondents’ eye-tracking data were then overlaid with features that were automatically identified in the video, such as trees, the path and man-made objects such as lamp-posts. Our analysis required every tree, rock, shrub, pathway, seat, person and sky regions to be automatically segmented out, as shown below, and then data from these regions collated.

In Royal Park, one of the drier-looking grassland-featured parks, the study showed that overwhelmingly respondents spent more time looking at man-made objects, relative to their appearance in the video. As an example, the figure below shows the proportion of different elements in the video for Royal Park. The next figure shows the relative amounts of time respondent A spent looking at those elements.

On the other hand, in Fitzroy Gardens with its dense green foliage, participants spent much more time looking at the bushes. In this case man-made objects weren’t as salient.

This seemed to correlate with the opinions that respondents had of the parks. In our study, Fitzroy Gardens came out as the favourite park with its lush green foliage, abundant bird sounds and water features.

Using data in this way will allow researchers to analyse and identify what matters to users of outdoor spaces. Urban decision-makers will be able to use this information to better refine urban design, signage and safety.

Observation as a means of control

At the same time, with eye trackers becoming cheaper and more ubiquitous, the collection of this kind of data could become a double-edged sword.

Studying what we “eye-ball” is of keen interest to advertisers. In academic research, subjects know we are watching what they look at, as do the users of Google Glasses or Microsoft’s Hololens. However, we may be unaware of how data from our eyes are gathered by other means, as spying mannequins demonstrate .

In 1791, the English philosopher Jeremy Bentham coined the term “panopticon”: an inspection house that allowed guards to see all cells in a prison, while remaining hidden from view. Although few prisons with panopticons were ever built, they became an essential concept for the analysis of cities and government during the 20th century.

French philosopher Michel Foucault argued that a panopticon ably maintains social and power imbalances while using that most passive method of control: observation. As governments and private corporations increasingly use eye-tracking data, everyone can act as observers, recorders and the observed – whether they intended to or not.

In this sense we could argue that the increasing development of eye tracking could usher in the age of the mass panopticon. Yet, the relationship between a selfie society, an “all-seeing, all-knowing” culture and the future of eye tracking in open domains remains to be “seen”.

Jodi Sita and Marco Amati will discuss the study findings in a presentation at the RMIT city campus from 2.30-3.30pm on Tuesday, August 23. You can register to attend here.