The president of the US has struggled recently to convey the sense that he is familiar with the details, or even broad outline, of his own country’s history. It’s therefore unlikely that he’s au fait with the politics of France’s King Louis XIV – even if he does emulate the Sun King’s interior design style. But if the struggling president wants to overhaul his governing style and truly enhance his power, he’d do well to look further into a character in whose era he might have felt at home.

As Trump builds (and rebuilds) his ramshackle executive team, his administration is unmistakably taking on the characteristics of a royal court. From the appointment of close relatives to the ever-shifting lines of cabals, the dubious credentials of some aides – and the even shadier connections of others – the White House has taken on the volatile, sensitive and often opaque nature of courtly life in the medieval and early modern period. The Oval Office now comes complete with pretenders, émigrés, favourites, figures with dubious foreign connections – and, most unusually, a jester in charge.

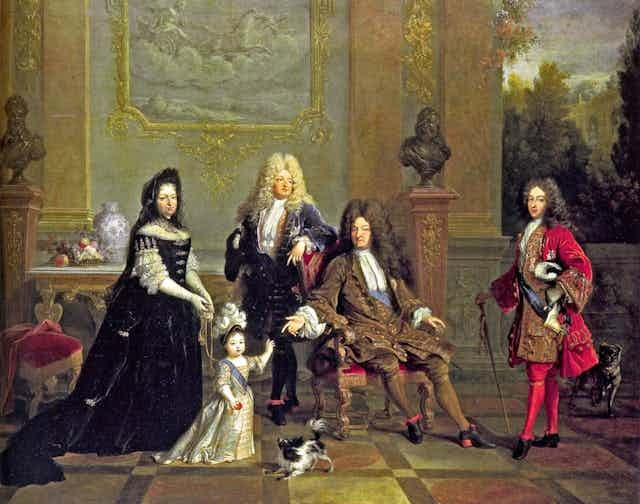

With one American comedian going so far as to evoke the guillotine (to her immediate regret), the example of the French monarchy appears to stalk Donald Trump. From reports of White House factionalism and infighting to the president’s assertion that he has the “absolute right” to share whatever information he likes on behalf of the US, the West Wing increasingly resembles the court of Versailles.

Sadly for Trump, he seems only to take personal inspiration from the Sun King when presented with fabric swatches. Instead, he would do well to acquire the principal skill that helped the French court set the standard for diplomacy and negotiation in the latter half of the 17th century: subtlety.

Stature over statute

The court system was extremely sensitive. The slightest of gestures could signal the rise or fall of any particular courtier; a mere glance, the nod of a head, or a seemingly polite enquiry about somebody’s whereabouts could be enough to tell the rest of the court that their star was in the ascendant or that the sun had set on their favour. Courtly protocol became a universal language – and French grew as the language of diplomacy across the European continent.

This behaviour was gentle in performance only, as its true meaning could be as forceful as crushing the bones in your opponents’ hands. If Trump, like the rest of 18th-century Europe and beyond, took some inspiration from these standards, it would, at least, spare the metacarpals of foreign leaders, whose schedules must now surely include a daily session with a grip strengthener in preparation for the president’s infamous handshake.

The power of the office of the president depends to some extent upon the charm and persuasion of the incumbent. The commander-in-chief’s ability to cajole undecided members of the House or the Senate by making a well-timed phone call is just one way the aura of the office can be employed to effect political change. Trump’s braggadocio robs him of this subtle form of presidential influence – an un-legislated, unofficial aspect of legitimate power that relies not on statute, but on stature.

The French court not only understood this sort of power, but also redefined it. Louis XIV, through both longevity and innovation, re-crafted not just the image of European monarchy, but the very idea of what constituted a public figure. Even the minutiae of his daily habits became performances designed to reinforce the glory of the crown; the intricacies of daily life at the court made for a reality show of sorts, with the king cultivating an early form of celebrity.

The two Trumps

The historian Ernst Kantorowicz famously wrote of “the king’s two bodies” – the idea of a monarch as the marriage of a mortal physical body with a mystical, eternal body politic. This was never better embodied than by Louis XIV, a man who made even the most mundane of bodily functions representative of royal power. The indivisibility of the self and the office was a given.

The importance of taking the two together seems to be lost on Trump and his coterie. While the Sun King did well in uniting these two bodies, the president can barely contain two Twitter accounts – and it’s clear from both handles which one holds sway.

The once mighty @POTUS account is merely an offshoot of the long-running @realDonaldTrump, a more lovingly maintained feed. It’s regularly updated with the latest pictures of the president in action, and time and again, it goes against the presidency’s official statements, often ending up directly at odds with the government’s given line. The distinction between the two accounts is emblematic of the gap that exists between Trump’s apparent views of public service and private interest.

This is not merely an academic distinction. The president’s dual existence as a public and private individual has constitutional consequences – not least when it comes to his family appointments or myriad potential conflicts of interest.

Democratically appointed leaders generally do well to avoid suggesting any quasi-divine foundation for their positions, but they should at least understand that so long as they hold office, their private selves and their public roles become one and the same. They do not get to operate as two separate public and private entities. It seems Trump simply doesn’t understand this concept – and much less, how important it is. It should therefore come as no surprise when he struggles to grasp the principle of the separation of powers, or dismisses investigations into his firing the FBI director as a “witch hunt”.

To paraphrase Louis XIV’s famous words: for the time being, Mr President, “L’état, c’est toi.”