Articles on Medical records

Displaying all articles

If it can happen to a future queen, it can happen to you. Maybe it already has.

There are many uses for digital systems that are not centrally controlled and that allow large numbers of people to participate securely, even if they don’t all know and trust each other.

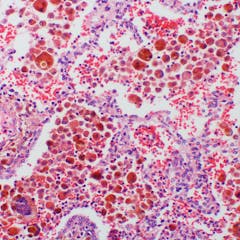

In health care crises, researchers can avoid waiting for clinical trial results by using data from health care systems to analyze the effectiveness of treatments for COVID-19 and other illnesses.

While the HIPAA Privacy Rule prevents health care providers from sharing your health information without your permission, it doesn’t prevent other people from asking you about it.

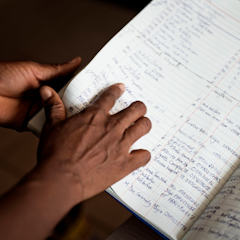

Decoding doctors’ writing can unlock vital health data.

A health law expert explains what the regulation does and doesn’t protect.

Past upgrades to the state’s medical record system have cost tremendous amounts of money, and on at least one occasion, forced clinicians to revert to paper-based methods.

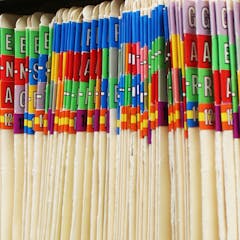

Patient information dumped on the side of the road in Brisbane recently has raised the issue of how hospitals and clinics manage their old paper records.

New laws mean My Health Record data is more protected than other patient data. Privacy policies should be the same across the board.

What if you never had to pick up a medical record or image from one doctor to take to another? That capability already exists, but it’s not being well-utilized. Here’s a look at why.

If you’re opting out of My Health Records, you’re opting in to “business as usual”. Here’s what the current system looks like.

Unless you take action to remove yourself before October 15, the federal government will make a digital copy of your medical record, store it centrally, and give numerous people access to it.

My Health Record is a step towards empowering patients with greater knowledge about their health – and could help save lives in emergencies.

Medical practices have special requirements under the Privacy Act, but the security and privacy systems some providers currently have in place may be inadequate.

Non-use of data may be an even bigger problem that its misuse.

Political and community leaders must act now to preserve the American middle class and adapt the US economy for the 21st century.

Most people know they can donate their organs after they pass away. But what about their medical data? For National Donor Day, we suggest countries create national databases of data donors.

Data-privacy advocates may have won the care.data battle, but it looks like they’re about to lose the war.

There are advantages, too.

Looking at historical health-care records can reveal how misunderstanding of a medical condition first came to develop and why it may not be being treated properly.