The Australian television satire Utopia invited the public along for a laugh that architects and planners have been sharing for decades. We laugh at the idea of utopia to disassociate ourselves from the disasters brought on by utopian visions.

Le Corbusier’s is perhaps the most famous. He dreamt of people living in racks of council flats rather than old building stock on the ground.

The only architects who have not gotten too savvy to dream of utopias are men in their nineties who missed the change in public opinion.

Jacque Fresco hopes one day that machines will build mega-structures while we humans relax. Paolo Soleri’s hyper-dense prototype, Arcosanti, remains permanently stalled with 97% of the work incomplete.

These examples are goofy-faced totems for a demon that we actually fear. Serious architectural writers bring up examples like Albert Speer’s plan for Berlin and concentration camps.

Karl Popper cemented the association between utopianism and totalitarianism. Writing in 1957 after making a name for himself as a critic of Marxist epistemology, he said social engineering (especially of the Marxist variety) was despotic, delusional and — you guessed it – utopian. The word has had Orwellian overtones ever since.

Our urban landscapes have utopian pedigrees

That’s fair enough if we’re talking about religious or ideological utopian visions. Urban planning is different. It depends on utopian visions as touchstones. Urban planners need to be granted a unique dispensation and allowed to talk in utopian strains.

One reason was explained by architectural writers David Gosling and Barry Maitland. While acknowledging Popper’s concerns, they argued that utopian visions in urban design are catalytic – never mind the handful of fools who treat them as prescriptions. Utopian visions bring clarity to real-world debates, they argued, “by postulating alternative hypotheses in a pure and crystalline form”.

Another theorist, Françoise Choay, argues the enterprise we call urbanism would not exist without utopian models. All urban theories, she says, have been indelibly stamped by past utopian models.

Surely that can’t be true of urban theories today, when architects and urban planners laugh at a show called Utopia? It is undeniably true. Current urban theories have utopian pedigrees, some now 100 years old.

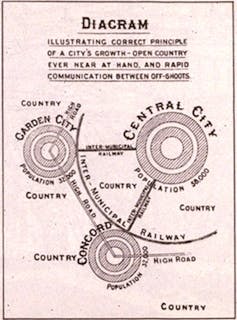

Take the principle of consolidating development within walking distance of train stations: it has been indelibly stamped by Ebeneza Howard’s circular diagram for transit-based “garden cities”.

Less flatteringly, our permissiveness of ongoing sprawl betrays the indelible stamp of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Broadacre City. Wright thought the natural outworking of personal mobility machines (cars) was that every person should get enough land of their own to pretend they are farmers.

Most embarrassing of all are our inner-city apartments. Built over batteries of multi-storey car parking, and beside roads that look like great venues for Formula One racing, most bear the indelible stamp of the General Motors “Highways and Horizons” pavilion with its Futurama exhibition at the 1939 World’s Fair in New York.

Rarely these days are utopian visions rolled out all at once. They are more typically in the background, like the rules of a game, informing piecemeal implementation.

Many of us will have had firsthand experience with one, the Broadacre game, if ever we have built a house on a large block of land. We would have asked ourselves how the car could be parked between the kitchen and road, and what travel times (never mind distances) that road could promise to roadside amenities.

Velotopia: a new vision

As two authors who choose to rely on our bikes for most of our transport, it bothers us that the rules of our game are not well understood. When we choose where to live, shop, work or send our children to school, we don’t care so much about walking distances, the frequency of public transport or congestion on roads. We want to know where the cycleways are.

Cycleways tend to follow historic rail easements and waterways. This means that as cyclists our cognitive maps of most cities are dominated by the flatlands on the wrong side of the tracks that these cycleways often pass through. Ironically, it is often these very flatlands that, in time, become the new sites for “starchitect” development.

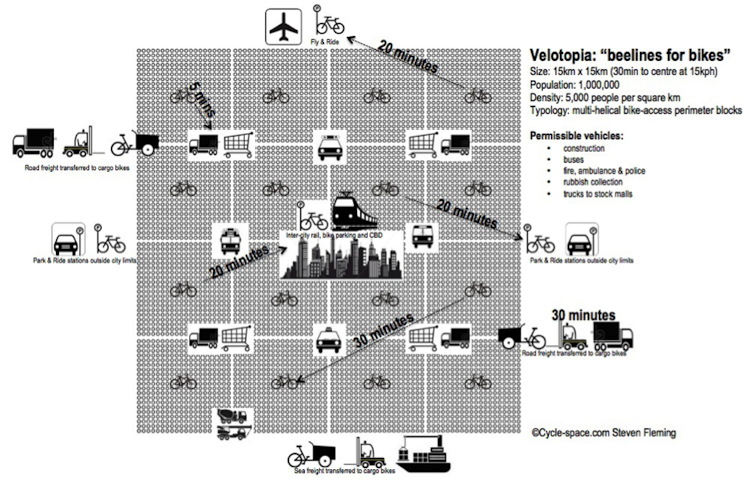

We want to offer a new utopian dream. It is not borne of signature buildings but rather built on a bicycle-oriented lifestyle and informed by a utopian dream we call Velotopia.

In its crystalline form, Velotopia uses pedal power for virtually everything, even taxis and freight — a trend in European town centres already. In this utopia, cyclists cover 10-kilometre trips in 30 minutes of safe and social bliss. There to meet them at both ends are secure and convenient bike-parking facilities inside most buildings; our bikes are as welcome as wheelchairs or prams.

We’re not asking that the rules of our game obliterate those of car lovers, walkers or straphangers. We’re simply following the conventions of our disciplines to imagine that our cities could accommodate an extra utopian dream, one that creates a safe cycling space. Put like that, it is a remarkably simple and profoundly utilitarian ask.

Our work is to bring Velotopia into plain view, as a catalytic vision. Some of our ideas for bike-access building types and ground planes designed to prioritise cycling will be on display in the Queensland Museum in Brisbane from November 28, 2014, to June 2015, as part of the National Museum of Australia’s Freewheeling exhibition. In late November we will meet policymakers in Brisbane to explore the principles of Velotopia as a catalyst for bicycle-orientated development.

As Velotopia becomes visible, we envisage a safer and more enjoyable cycling space, which can take its place among other utopias that influence the structure and spaces of our cities.