Drought, fires, floods, marine heatwaves – Tasmania has had a tough time this summer. These events damaged its natural environment, including world heritage forests and alpine areas, and affected homes, businesses and energy security.

In past decades, climate-related warming of Tasmania’s land and ocean environments has seen dozens of marine species moving south, contributed to dieback in several tree species, and encouraged businesses and people from mainland Australia to relocate. These slow changes don’t generate a lot of attention, but this summer’s events have made people sit up and take notice.

If climate change will produce conditions that we have never seen before, did Tasmania just get a glimpse of this future?

Hot summer

After the coldest winter in half a century, Tasmania experienced a warm and very dry spring in 2015, including a record dry October. During this time there was a strong El Niño event in the Pacific Ocean and a positive Indian Ocean Dipole event, both of which influence Tasmania’s climate.

The dry spring was followed by Tasmania’s warmest summer since records began in 1910, with temperatures 1.78°C above the long-term average. Many regions, especially the west coast, stayed dry during the summer – a pattern consistent with climate projections. The dry spring and summer led to a reduction in available water, including a reduction of inflows into reservoirs.

Is warmer better? Not with fires and floods

Tourists and locals alike enjoyed the clear, warm days – but these conditions came at a cost, priming Tasmania for damaging bushfires. Three big lightning storms struck, including one on January 13 that delivered almost 2,000 lightning strikes and sparked many fires, particularly in the state’s northwest.

By the end of February, more than 300 fires had burned more than 120,000 hectares, including more than 1% of Tasmania’s World Heritage Area – alpine areas that had not burnt since the end of the last ice age some 8,000 years ago. Their fire-sensitive cushion plants and endemic pine forests are unlikely to recover, due to the loss of peat and soils.

Meanwhile, the state’s emergency resources were further stretched by heavy rain at the end of January. This caused flash flooding in several east coast towns, some of which received their highest rainfall ever. Launceston experienced its second-wettest day on record, while Gray recorded 221 mm in one day, and 489 mm over four days.

Flooding and road closures isolated parts of the state for several days, and many businesses (particularly tourism) suffered weeks of disruption. The extreme rainfall was caused by an intense low-pressure system – the Climate Futures for Tasmania project has predicted that this kind of event will become more frequent in the state’s northeast under a warming climate.

Warm seas

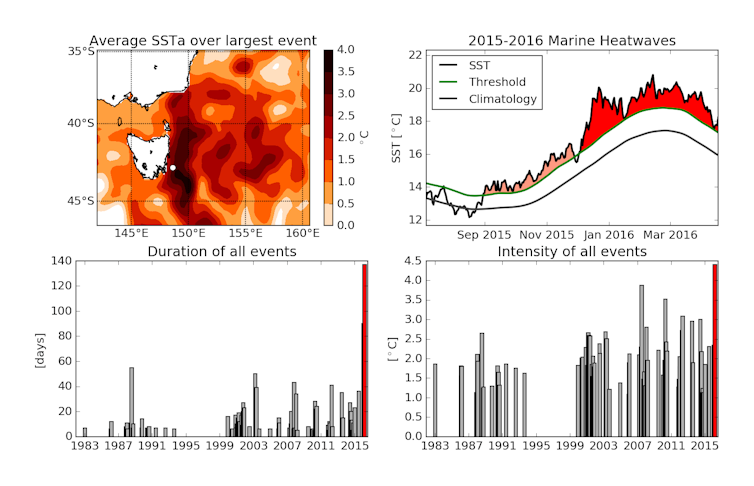

This summer, an extended marine heatwave also developed off eastern Tasmania. Temperatures were 4.4°C above average, partly due to the warm East Australian Current extending southwards. The heatwave began on December 3, 2015, and was ongoing as of April 17 – the longest such event recorded in Tasmania since satellite records began in 1982. It began just days after the end of the second-longest marine heatwave on record, from August 31 to November 28, 2015, although that event was less intense.

As well as months of near-constant heat stress, oyster farms along the east coast were devastated by a new disease, Pacific Oyster Mortality Syndrome, which killed 100% of juvenile oysters at some farms. The disease, which has previously affected New South Wales oyster farms, is thought to be linked to unusually warm water temperatures, although this is not yet proven.

Compounding the damage

Tasmania is often seen as having a mild climate that is less vulnerable to damage from climate change. It has even been portrayed as a “climate refuge”. But if this summer was a taste of things to come, Tasmania may be less resilient than many have believed.

The spring and summer weather also hit Tasmania’s hydroelectric dams, which were already run down during the short-lived carbon price as Tasmania sold clean renewable power to the mainland. Dam levels are at an all-time low and continue to fall.

The situation has escalated into a looming energy crisis, because the state’s connection to the national electricity grid – the Basslink cable – has not been operational since late December. The state faces the prospect of meeting winter energy demand by running 200 leased diesel generators, at a cost of A$43 million and making major carbon emissions that can only exacerbate the climate-related problems that are already stretching the state’s emergency response capability.

Is this summer’s experience a window on the future? Further study into the causes of climate events, known as “detection and attribution”, can help us untangle the human influence from natural factors.

If we do see the fingerprint of human influence on this summer, Tasmania and every other state and territory should take in the view and plan accordingly. The likely concurrence of multiple events in the future – such as Tasmania’s simultaneous fires and floods at either end of the island and a heatwave offshore – demands that governments and communities devise new strategies and mobilise extra resources.

This will require unprecedented coordination and cooperation between governments at all levels, and between governments, citizens, and community and business groups. Done well, the island state could show other parts of Australia how to prepare for a future with no precedent.