This article was co-authored by Kathleen Musulin, a Malgana/Yawuru woman living in Carnarvon and a member of the Carnarvon Shire Council lock hospital memorial working group.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers are advised that this article contains images of deceased people.

In February 1911, Perth newspapers published detailed reports about lock hospitals, where Aboriginal people said to have “venereal diseases” were incarcerated on two remote islands off the coast from Carnarvon, Western Australia.

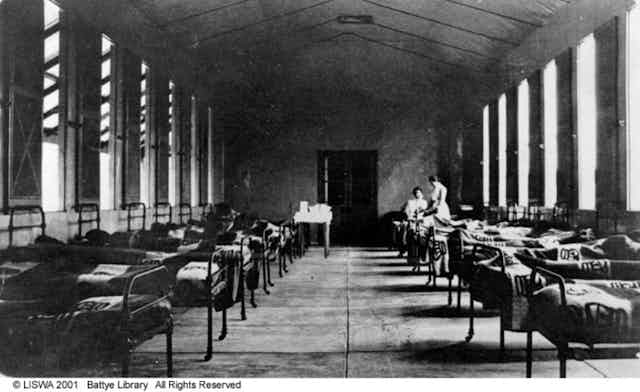

The articles recorded that 55 operations were conducted under anaesthesia on Bernier and Dorre islands during the year to June 30, 1910, in rough, makeshift conditions. Several inmates were also subjected to unsuccessful experimentation with a “vaccine” containing arsenic compounds that had previously been tested on British soldiers with syphilis.

Sourced from the medical superintendent’s annual report, the articles also told of difficult, often dangerous conditions sailing to the islands, the delivery of mail and stores, visits of inspection by government officials and others, and the hard work done by Aboriginal inmates on the islands.

Arrivals and departures of staff and patients were also recorded, with brief mention of Nurse “Batison” arriving on Bernier Island on February 7, 1910. Readers who saw the recent SBS documentary Who Do You Think You Are?, exploring the ancestry of musician Peter Garrett, will know that this reference was to his grandmother, Emily Bateson.

Further reading: Acknowledge the brutal history of Indigenous health care – for healing

Garrett and his grandmother shared birthdays – 70 years apart – and were close. But he cannot remember ever hearing her talk about the years she spent at the lock hospitals. His journey to Dorre Island earlier this year, retracing her footsteps, was one of emotional discovery.

Many people – including those working in the health sector – are likely to share Garrett’s shock in learning about the lock hospitals, which inflicted incalculable traumas on Aboriginal people, wrenching them away from families and country. Thus one family’s story can be seen as a metaphor for the wider invisibility of so much traumatic colonial history.

Equally, comments during the documentary by Carnarvon residents Kathleen Musulin, a Malgana/Yawuru woman (a co-author of this article), and Bob Dorey, a Yinggarda/Malgana man, are a reminder that these traumatic histories remain present in many peoples’ lives.

As with so much brutal colonial history that was subsequently written out of the textbooks through “systemic white ignorance”, many details about the lock hospitals were widely reported and publicly known at the time. Journalists visited them on a number of occasions, and detailed accounts were also written by other visitors, as well as one of the nurses.

A search of the National Library of Australia’s Trove database shows 274 newspaper articles mentioning the Bernier and Dorre lock hospitals during their years of operation, 1908-19. Fifty-seven per cent of these articles (157) were published in Perth-based newspapers, and 11% (31) were published interstate.

As the table shows, the intensity of newspaper coverage diminished as the years went on – coinciding with reduced staffing, resources and activity on the islands.

Overall, the coverage was largely positive about the lock hospitals, reflecting the dominance of official and government views, which accounted for about half of the sources. As well, glowing comments by the writer and researcher Daisy Bates appeared widely – in contrast to her later, more often cited assessments of the lock hospitals as “a ghastly experiment”, and Bernier and Dorre islands as “the tombs of the living dead”.

With the exception of a number of reports recording the high death rates on the islands, it is telling that most of the negative reports did not relate to concerns for the Aboriginal people. Instead, they tended to reflect concerns about cost or logistical difficulties. Some suggested that even more drastic measures should be used against Aboriginal people.

Other controversies included questions about the underlying rationale given for the hospitals, with reports suggesting that many inmates had ulcerative granuloma rather than syphilis. Professor Frank Bowden, an infectious diseases physician in Canberra who has seen photographs of patients with this condition that were published by a Carnarvon doctor in 1909, believes they most likely had what is now known as donovanosis, a now-rare disease that causes genital ulceration and can be spread by sexual and casual contact.

Some of these patients with granuloma were, however, injected with a new arsenic-based treatment for syphilis, Salvarsan, described as “magical” in Perth newspaper headlines. While it went onto become a successful and effective treatment, this early version of the drug, also known as “compound 606”, became known for its toxic side effects.

In latter years, when there were periods without a resident doctor on the islands, articles in the Carnarvon newspaper protested against the local doctor being called to attend the lock hospitals. Newspapers also recorded protests from Port Hedland residents about the last remaining patients from Bernier and Dorre being “dumped” in a lock hospital built there in 1919.

Despite the almost complete absence of Aboriginal people’s voices in the coverage, it is possible to discern something of their experiences. Visitors and staff on the islands often reported the “home-longing” of inmates. In a 1913 article, a Carnarvon resident commented:

Ever since the Lock hospitals were established, natives are on the alert whenever police or inspector appears, and as soon as any examination takes place, word is sent round the country and diseased natives are off into the bush.

When news broke of plans to close the hospitals, a Geraldton newspaper reported that Aboriginal people would be “greatly pleased” as “they looked on deportation to the islands with even greater aversion than a Russian regards enforced absence in Siberia…”

A nurse who wrote many articles about her time on the islands described medicine for rheumatism being made out of sandalwood, the women’s skills in hunting and making clothes, their cultural practices, and their pleasure in trying to teach her their languages. In one article, the nurse reproduces a song in an Aboriginal language that she said described the women’s “burning love” for their country.

Generally, however, the articles reveal the inability of white institutions and authorities to recognise and respect the humanity of Aboriginal people. Instead, they were pathologised, infantilised and dehumanised.

There was little distinction between the disease and the people, reflected in references to “this menace”, “these diseased pariahs”, and “the evil”. The newspapers’ framing of disease and Aboriginal bodies as one and the same supported and enabled discriminatory policies that promoted segregation and human rights abuses.

In one of the familiar patterns of colonisation, Aboriginal people themselves were often blamed for having diseases that had in fact been introduced. The traumatic impacts of the lock hospital policies were underplayed. Newspaper articles, like the official reports, routinely referred to “the collection” of people, a term that does not remotely convey the reality of forced removal from family and homelands, often in cuffs or chains.

Newspaper reports also show officials and others promoting the lock hospitals as humanitarian, benevolent work, while also acknowledging that Aboriginal people viewed them as a gaol and that force was required to recruit “patients”.

The lock hospital episodes can be seen as archetypal projects of colonisation, whereby the “narrative of benevolent intentions serves the state well in reproducing relations of domination and subordination” – a critique more recently made of income management.

The reporting of the WA hospitals is part of a larger story; research by Dr Lynore Geia (co-author of this article) in her home community on Palm Island has revealed the ongoing impact of the history of medical institutionalisation on nearby Fantome Island, as well as the effect of negative media coverage on peoples’ lives and well-being.

The lock hospital episodes and related governmental, professional and media discussions helped lay a foundation for a deficit-based portrayal of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people that continues to be seen across many spheres, often resulting in problematic policy “solutions”.

The 2007 NT Intervention has been identified as the ultimate example of media-driven policymaking, resulting in large part from the culmination of the “perfect storm” of media hysteria, conservative political agendas and policy opportunism.

Connections can be drawn through to the present day from the institutional racism of white structures of government and media that enabled the lock hospital policies. The impacts of racism in society’s most powerful institutions, including health care and the media, continue to affect adversely the health and well-being of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

Two of this article’s authors, as Indigenous women, have deep personal insights into the ongoing harmful impacts of negative media stereotyping and deficit-driven professional and public discourses. The other authors, as non-Indigenous women, acknowledge that our experience and understanding of these impacts is limited by the way mainstream institutions, including health care systems and the media, so often uphold our white privilege.

However, the deficit-framing of so much “whitestream” discussion is under challenge; Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander researchers are “writing back” and “changing the collective story of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities from one of deficit to one of strength and resilience”.

Contemplating the history of the lock hospitals gives those of us working in health, media and communications an opportunity to recognise and acknowledge the impacts of our fields’ practices, in the past and present, and to create stories that enable healing, rather than hurt. Moving forward in our respective practices involves acknowledging history, changing the narratives from deficit to strengths, and building better outcomes in real partnership and collaboration.