Girls in primary school are just as physically capable as their male classmates, according to our research, taking the sting out of the insult “you play like a girl”.

When we compared primary school children’s physical capabilities, differences between girls and boys were not as important as people think. So, they should be happily playing with and competing against each other in the backyard, playground and sporting fields.

Read more: It's not just the toy aisles that teach children about gender stereotypes

As part of wider research to assess people’s physical capabilities across the lifespan, we tested 300 children and adolescents between the ages of 3 and 19.

We tested each child for over two hours, taking more than 100 measurements. These included measuring the strength of 14 muscle groups, the flexibility of 13 joints and 10 different types of balance. We looked at factors including hand dexterity, reaction times, how far kids could walk, how high and how long they could jump, as well as their gait.

What did we find?

Across all measures of physical performance, there was one consistent finding. There was no statistical difference in the capabilities of girls and boys until high-school age (commonly age 12).

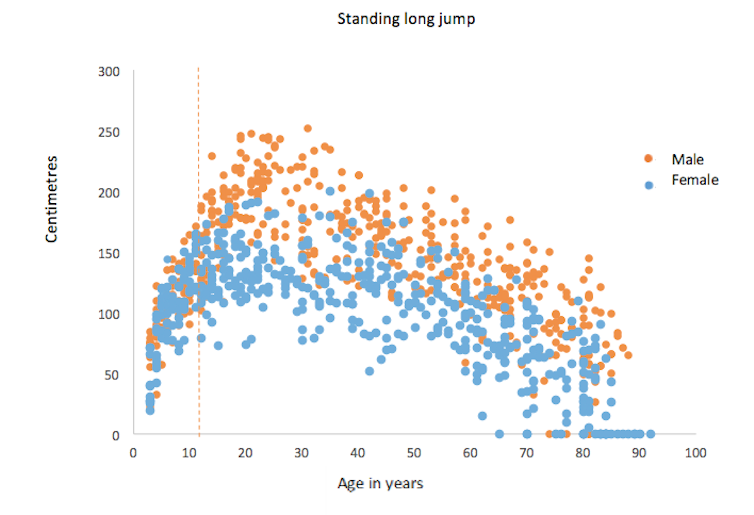

Let’s use standing long jump (also known as a broad jump test) as an example. This provides a measure of your legs’ explosive power. It needs minimal equipment and the results compare well with the type of information you get from strength testing using expensive equipment. It’s also one of the tests would-be American NFL (National Football League) players take to impress talent scouts.

We found no difference between boys and girls before they turn 12 (see graph below). Every physical measure followed this pattern.

How do our findings compare?

Other studies have had similar results. These have included ones testing muscle strength, walking, jumping and balancing.

However, it’s difficult to directly compare data from one study to another, as different studies have different sample sizes, include children of different age ranges, and assess different measures. For example, we were the first to use the timed stairs test and stepping reaction time to find what regular children were capable of.

Some studies found differences in physical capabilities between primary school-aged boys and girls using the same types of tests we used. And others reported small differences in the jump height of boys and girls aged 6-17 years but not with the long jump.

These differences can in part be attributed to sampling methods that were limited to specific age ranges or locations and socioeconomic backgrounds, the latter potentially having a significant impact on physical health and activity.

By contrast, the children in our research were generally representative of the Australian population, using data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics about socioeconomic status, ethnicity and body mass index.

What do our findings mean for kids, coaches and parents?

There is no consensus across schools or among different sports about mixed-gender sports for primary school children.

For instance, boys and girls compete separately in most local Little Athletics after age five but field hockey can have mixed gender teams until age 17.

And in tennis, primary school-aged girls and boys play separately in singles matches but can play against each other in mixed doubles.

Our findings support the push for boys and girls to compete in mixed sporting teams until the end of primary school, after which the hormonal changes of puberty mean boys tend to perform better in sports and tasks requiring strength and speed.

Read more: Our 'sporting nation' is a myth, so how do we get youngsters back on the field?

There are also some practical advantages to mixed sport in primary school and in weekend competitions:

- fewer scheduling conflicts for councils (allowing school and sport administrations to fit games more conveniently into busy sporting venues)

- fewer clubs or organisations to share already stretched government and private sector funding

- consolidation of coaching and manager talent, and most importantly

- fewer parent-taxi drop offs.

Perhaps perceived differences in physical capability between boys and girls are based on outdated gender stereotypes that appear at birth, when some boys are given their first footy and some girls their first doll.

But whatever the origin of the idea young boys are physically more capable than young girls, the evidence is clear. Boys “play like a girl”, and that’s certainly no insult.