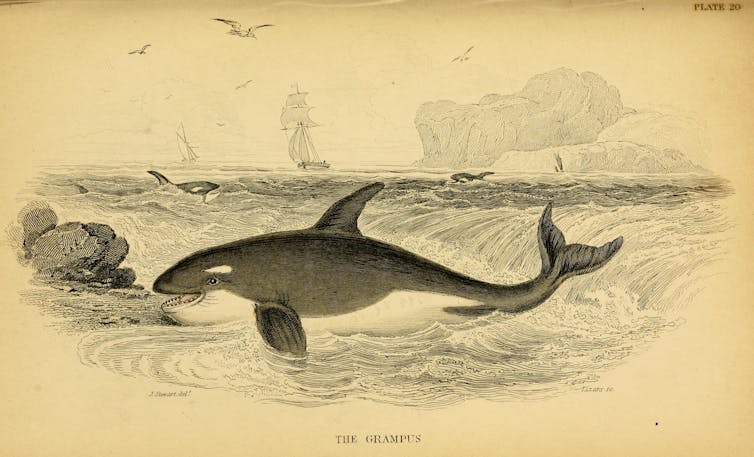

Travel back with me a few hundred years to before the industrial revolution, and the wildlife of Britain and Ireland looks very different indeed. Take orcas: while there are now less than ten left in Britain’s only permanent (and non-breeding) resident population, around 250 years ago the English cleric and naturalist John Wallis gave this extraordinary account of a mass stranding of orcas on the north Northumberland coast:

Sixty-three of them came on shore at Shorestone, 29th July 1734, about noon – 60 of which were between 14 and 19 feet long, and the other three about eight feet. They were all alive when they came on shore and made a hideous noise, but they were soon killed by the country people, who removed them one by one with six oxen and two horses, and made about ten pounds by their blubber. The same kind of noise was heard in the sea the night before by the shepherds in the fields, when it is supposed they were sensible of [the orcas’] distress in shoal-water.

If this record is reliable, then more orcas were stranded on this beach south of the Farne Islands on one day in 1734 than are probably ever present in British and Irish waters today. In his natural history of Northumberland, Wallis describes the orca as a “great enemy to the whale” and waging fierce battles with common thresher sharks, which use their long tails as weapons.

Other careful naturalists from this period observed orcas around the coasts of Cornwall, Norfolk and Suffolk. I have spent the last five years tracking down more than 10,000 records of wildlife recorded between 1529 and 1772 by naturalists, travellers, historians and antiquarians throughout Britain and Ireland, in order to reevaluate the prevalence and habits of more than 150 species for my new book, The Atlas of Early Modern Wildlife.

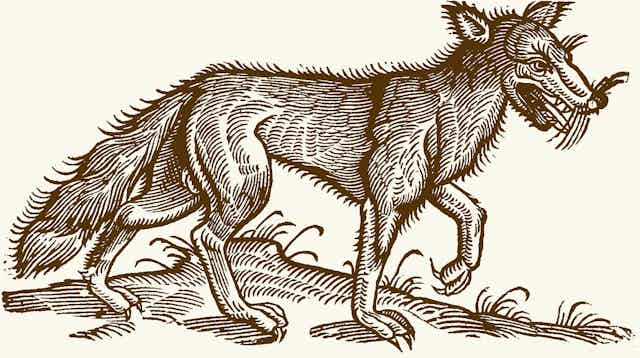

In the early modern period, wolves, beavers and probably some lynxes still survived in regions of Scotland and Ireland. By this point, wolves in particular seem to have become re-imagined as monsters, looming around every corner in the imaginations of writers such as Robert Gordon of Gordonstoun:

The violence and numbers of most rapacious wolves … prowling about wooded and pathless tracts causing great loss of beasts and sometimes of men, are such that, driven from almost all the rest of the island, they seem to have fixed their lairs and their homes [in Strathnaver]. Assuredly, they are nowhere so plentiful.

Elsewhere in Scotland, the now globally extinct great auk could still be found on islands in the Outer Hebrides. Looking a bit like a penguin but most closely related to the razorbill, the great auk’s vulnerability is highlighted by writer Martin Martin while mapping St Kilda in 1697:

The stateliest as well as the largest of all the fowls here … stands stately, its whole body erected, its wings short. It flieth not at all, and lays its egg upon the bare rock which, if taken away, it lays no more for that year.

While white-tailed eagles, bustards and cranes were also all much more common than they are today, some other now-ubiquitous species were much less common before the industrial revolution. Rabbits were still mainly a coastal species except in lowland England, and roe deer were found wild only in the north of Scotland and Eryri (Snowdonia) in north-west Wales. There were no grey squirrels, and brown rats were only introduced at the very end of the period.

On the other hand, red squirrels and ship rats were still widespread, and pine martens and “Scottish” wildcats were also found in England and Wales. Fishers caught burbot and sturgeon in both rivers and at sea, where they also pulled in plentiful amounts of tuna and swordfish, as well as now-scarce fishes such as the angelshark, halibut and common skate. Threatened molluscs like the freshwater pearl mussel and oyster were also far more widespread.

However, despite the abundance and diversity of wildlife at this time, the authors of my sources were not what I would call conservationists. In many ways, they had more in common with modern game hunters and anglers, in that they often fished and shot, and they valued wildlife as a resource and for recreation, rather than recording it in order to help preserve it.

Britain’s early naturalists

From the early 16th century to the late 18th, the prevailing belief was that God had furnished Britain and Ireland with wildlife to serve human needs. Animals were valued as food, medicine and for the “services” they could provide, including pest control and lawn mowing.

Scholars today sometimes describe our current era as the Anthropocene – the period in Earth’s history when humans dominate the planet’s natural systems. While the question of when, exactly, this period started is really for geologists and climate scientists, the naturalists writing 250-500 years ago do already show evidence of “Anthropocene-thinking”.

Most of the sources I have read demonstrate an unequivocal belief in humans’ rightful domination of nature. These authors can be called “naturalists”, in that they were writing natural histories, but their interest in wildlife was very utilitarian. Many describe refining their methods to produce higher yields in farming and fishing, while others are fascinated by the opportunities presented by discovering new natural resources.

This article is part of Conversation Insights

The Insights team generates long-form journalism derived from interdisciplinary research. The team is working with academics from different backgrounds who have been engaged in projects aimed at tackling societal and scientific challenges.

Naturalists travelling outside Europe in this period commonly used slave trading routes and vessels to sail, raised money for their collections via the slave trade, and wrote descriptions of foreign lands partially in the hope they could be exploited for profit as colonies and plantations. In the accounts of these naturalists, the obsession with finding gold displayed in the earlier journals of Christopher Columbus had blossomed into a general mania for cataloguing the natural resources of the Earth.

Predators such as wolves that interfered with human happiness were ruthlessly hunted. Authors such as Robert Sibbald, in his natural history of Scotland (1684), are aware and indeed pleased that several species of wolf have gone extinct:

There must be a divine kindness directed towards our homeland, because most of our animals have a use for human life. We also lack those wild and savage ones of other regions. Wolves were common once upon a time, and even bears are spoken of among the Scottish, but time extinguished the genera and they are extirpated from the island.

The wolf was of no use for food and medicine and did no service for humans, so its extinction could be celebrated as an achievement towards the creation of a more civilised world. Around 30 natural history sources written between the 16th and 18th centuries remark on the absence of the wolf from England, Wales and much of Scotland. Of these, the 17th-century text by Sibbald, a physician based in Edinburgh, is notable for using a network of correspondents based across Scotland and beyond. He invited responses to the following questionnaire:

I. What the Nature of the County or place is? And what are the chief products thereof?

II. What Plants, Animals, Mettals, Substances cast up by the Sea, are peculiar to the place, and how Ordered?

III. What Forrests, Woods, Parks? What Springs, Rivers, Loughs? With their various properties, whether Medicinal? With what Fish replenished, whether rapid or flow?

Sibbald was one of a handful of authors to use the so-called Baconian method of natural history inquiry, inspired by the “father of empiricism” Francis Bacon. Bacon used specific research questions to focus his observations and experiments, and this method was further developed by Robert Boyle into a natural history survey which could be given to travellers. Sibbald circulated his questionnaire to educated people across Scotland, then compiled the data in a manner which I and others have compared to modern crowd-sourced citizen science.

Much like Sibbald’s natural history, the writing of Richard Pococke, bishop of Ossory in southern Ireland in the mid-18th century, was informed by people he met on his travels. He writes in a style thick with detailed descriptions and local curiosities, so that readers can imagine travelling with him and stopping to study the landscapes, buildings and ruins along the way.

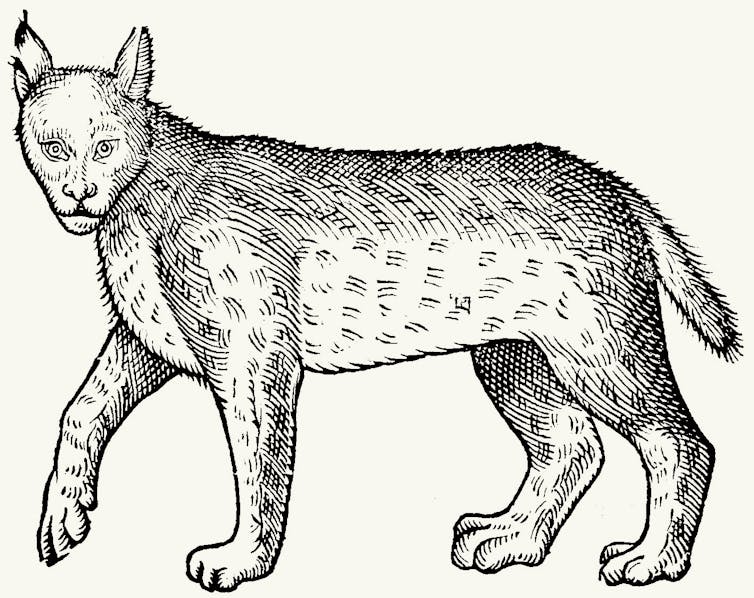

In Pococke’s 1760 Tour of Scotland, he describes being told about a wild species of cat – which seems, incredibly, to be a lynx – still living in the old county of Kirkcudbrightshire in the south-west of Scotland. Much of Pococke’s description of this cat is tied up with its persecution, apparently including an extra cost that the fox-hunter charges for killing lynxes:

They have also a wild cat three times as big as the common cat. They are of a yellow-red colour, their breasts and sides white. They take fowls and lambs, and brede two at a time … It is said they will attack a man who would attempt to take their young ones, but (men) often shoot them and take the young. The country pays about £20 a year to a person who is obliged to come and destroy the foxes when they send to him.

Strikingly, unlike earlier possible accounts of the Scottish lynx,, there is no celebration of the animal’s fur in this passage. Pococke’s informants simply seem to have thought of the animal as an annoyance which needed to be hunted out of existence – which soon afterwards, it was. Based on Pococke’s description, I think the loss of the lynx would have been celebrated by locals as much as the loss of the wolf.

Early concerns about species decline

The early modern environment was hardly a pristine wilderness. Almost every part of Britain and Ireland was regularly visited and, to differing degrees, exploited by human inhabitants.

This period also had its own climate crisis. The “little ice age” was a period of very cold weather that affected the North Atlantic region, in particular between 1550 and 1700. The growing season was typically three weeks shorter, there were severe famines in some decades, and there are accounts of sea ice off the coast of southern England.

The change was almost certainly not caused by humans, and was not nearly as severe a phenomenon as modern global heating is likely to become over the next century – but it nevertheless had a noticeable impact on the countries’ wildlife.

One important witness of its effects was Hugh Leigh, a minister based on Bressay in the Shetland Isles and correspondent for Sibbald’s Scotia Illustrata at the end of the 17th century. Clergymen often contributed to scientific research in this period because they were literate, had university degrees, and had time to pursue such interests as writing about wildlife.

Leigh, who wrote an especially detailed account of Bressay, Shetland’s fifth-largest island, would probably have been shocked to hear us praise the 17th century as a time of great biodiversity in Britain. His writing shows how concerned he was, in particular, about the decline of fish stocks in the waters around his home:

In old time the sea about this Coast was well stored with all common sort of fishes, as Mackerels, Herrings, Lings, Cods, Haddocks, Whiting, Sheaths, but especially with Podlines – young Sheaths which in fair weather would come so near to the shore that men and children, from the Rocks with Fishing-rods, could catch them in abundance. But all kinds of Fishing is greatly decayed here, notwithstanding that greater pains is taken by the Fishers now than ever before, who with small Norway Yoolls, two or three men in each of them, will adventure to the far sea and oft times endure hard weather.

Leigh is writing near the height of the little ice age, which I think explains his description of “greatly decayed” fish stocks. Cod in particular need temperatures of 3–7°C to breed, and we know that the cod fisheries also failed off Iceland, Norway and the Faroe Islands between the 1680s and 1700s.

The decline of cold-sensitive species would likely have had a complicated impact on more cold-hardy species – many marine fishes have an exact isotherm preference, so would have moved to deeper or shallower water, or north or south, in response to changing water temperatures. The end result seems to have been significantly reduced fisheries around Shetland for some time, although Leigh would never learn the explanation for the changes he was observing.

Other writers did, however, propose a range of explanations for the changes in fish stocks. For example, Hector Boece, a 16th-century historian with a flair for the dramatic, describes the loss of the herring fishery near Inverness as being due to “divine wrath” against the town.

Later observers came up with more scientific explanations. In the 18th century, Dublin authors Walter Harris, a pensioned historian, and Charles Smith, a prolific author of natural histories, write of five possible explanations for the loss of herring fisheries around County Down. These include burning too much kelp or polluting the ocean with “garbage of fish” and other “offensive things”; marine mammals such as seals or whales eating all of the herring; and fishing vessels interfering with the fish immediately after spawning, or catching juveniles before they are ready to be caught.

Some of these explanations feel startlingly modern, as do some of the mitigations these two authors suggest in response – including introducing a minimum mesh size of one inch, and avoiding catching fish that have just spawned. Both measures would not be seem out of place in a modern fisheries management plan:

Trail Nets with narrow meshes are great Engines for the Destruction not only of the profitable Herring (which is allowable) but of the Cobbs and young Fry, which are of little Value. To which may be added the common Practice in most Places of taking up the Cobbs in Sieves and using them as Food, when Hundreds of them are scarce equal in Value to one full grown Herring. These Practices therefore should be reformed as much as possible, and the Nets, wherein the Fish are drawn, should have their Meshes an Inch square, that in taking the larger Fish the Fry may escape.

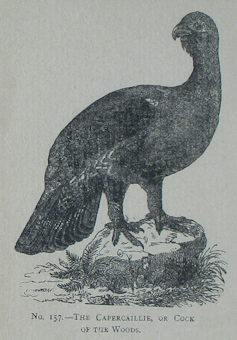

The capercaillie is another example of a species whose decline was correctly recognised by early modern writers. Today, this large turkey-like bird – famous for the males’ elaborate courtship rituals – is found only rarely in the north of Scotland, but 250–500 years ago it was recorded in the west of Ireland as well as a swathe of Scotland north of the central belt.

At the start of his 16th-century history of Scotland, John Lesley, then the bishop of Ross who made his career as a senior advisor to Mary Queen of Scots, describes the capercaillie as a delicious bird with “a gentle taste, maist acceptable” that could be found in Ross-shire and Lochaber – but only among woods of native Scots Pine.

Charles Smith, the prolific Dublin-based author who had theorised about the decline of herring on the coast of County Down, also recorded the capercaillie in County Cork in the south of Ireland, but noted:

This bird is not found in England and now rarely in Ireland, since our woods have been destroyed. The flesh is highly esteemed.

Despite being protected by law in Scotland from 1621 and in Ireland 90 years later, the capercaillie went extinct in both countries in the 18th century – due, according to these accounts, to the combined pressures of deforestation and hunting. It was successfully reintroduced to Scotland a century later, and the modern population is descended from these reintroduced animals.

Excitement for the ‘book of nature’

Nowadays, the popularity of bird watching as a hobby means these are the best-recorded species of animal in Britain and Ireland. In contrast, the best-recorded wild animals 250-500 years ago were mainly fish – from common freshwater species such as salmon, eel, trout and pike to the sea-dwelling herring, cod and oyster.

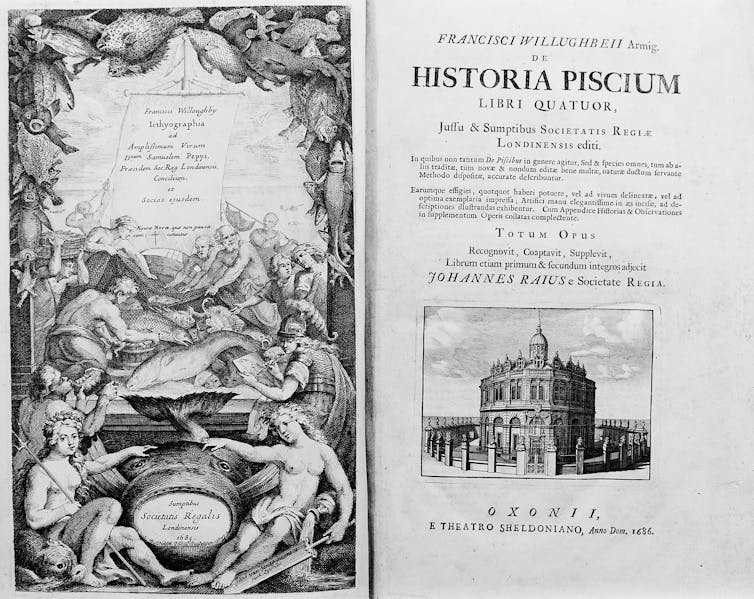

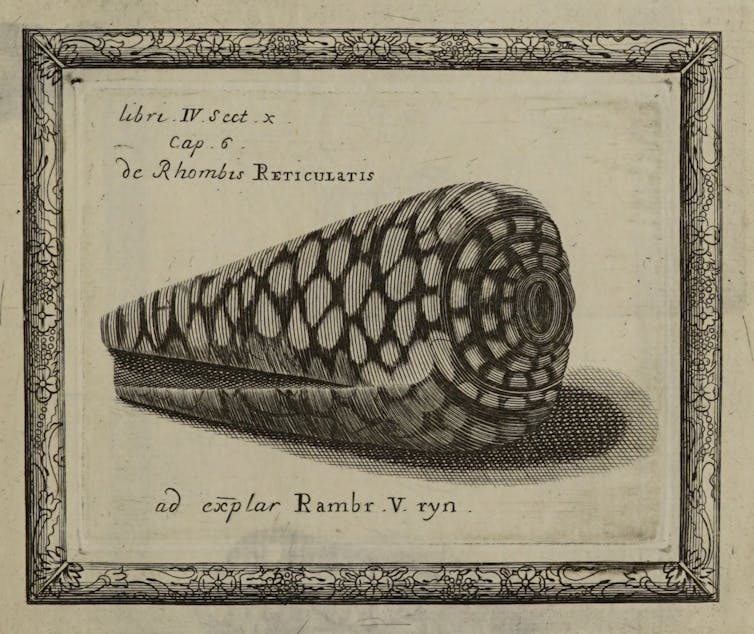

Some of the greatest scientists of the age were passionate about fish and the hobby of angling. Francis Willughby and John Ray devoted much of their lives to studying nature, and their De Historia Piscium (1686) includes more than 170 illustrations, drawn by Willughby and perhaps others, of the fish they describe with meticulous accuracy. Commercially, the book was a disaster, but the copies that remain today are a tribute to the increasing interest in ichthyology (the study of fish) during the 17th century.

Willughby and Ray’s canonical, illustrated handbooks – also on birds and quadrupeds and snakes – would later impress the Swedish botanist and zoologist Carl Linnaeus for their advanced taxonomy and close physical descriptions.

Other books were even more ambitious. Another of the most famous naturalists of the period, Martin Lister, included more than 1,000 illustrations in his Historiae Conchyliorum – essentially, volumes of scientific illustrations of molluscs, all shown in taxonomic order. The cost to hire an illustrator for this would have been prohibitive so Lister made it a family project, with his two teenage daughters, Susanna and Anna, completing the illustrations over a number of years. Lister closely supervised their work, sometimes demanding corrections if their sketches were not accurate enough.

Naturalists in this early-modern period prided themselves in not just repeating the observations of earlier writers, but consulting local informants and studying “the book of nature” for themselves. At times, the authors’ excitement for their field observations seems to jump off the page.

In 1713, Francis Nevill, a member of the Ulster gentry, wrote a letter published in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Nevill describes Lough Neagh – the largest lake on the island of Ireland – with mounting enthusiasm for its trees (“some of them have lain there some hundreds of years”), the healing quality of its water (“I look upon it to be one of the pleasantest bathing places I ever saw”), and its fish:

It does not abound with many sorts of Fish, but those there are are very good, such as Salmon, Trout, Pike, Bream, Roach, Eels and Pollans, with which last it does abound.

As well as hinting at a growing appreciation of nature “for its own sake”, rather than its utility for humans, records like this suggest some revisions are needed to the accepted narratives of species expansion in Britain and Ireland.

For example, the pike is normally considered to be an invasive species in Ireland, naturalised relatively recently. Yet the enthusiastic naturalists of early-modern Ireland record it widely – there are 15 records of it occurring on the island in the 17th century alone. This suggests it had been introduced, or perhaps even colonised, much earlier than previously suspected.

The plentiful “pollan” that Nevill describes is also noteworthy. At first, I thought his reference referred to the strange fish now known as the Irish pollan, which is a relic of the ice age most commonly found in Siberia, Alaska and Canada. Across western Europe, it lives exclusively in five loughs in Ireland.

However, Nevill goes on to describe his pollan as migrating to the sea, which makes that identification very improbable. Closer reading of this passage and others suggests that the name pollan at this time in fact referred to the saltwater shad. For such an important species, proper identification of historical records is vital.

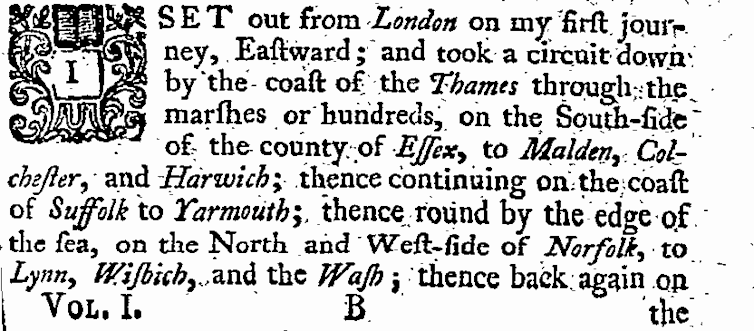

Excitement about local creatures was not only the purview of enthusiastic academics like Nevill. Travel writers often incorporated passages of nature writing too – none more famous than Daniel Defoe, author of Robinson Crusoe, who published his Tour thro’ the Whole Island of Great Britain between 1724 and 1726.

Almost 300 years later, it remains a much-admired source for historians studying this period – and Defoe’s descriptions are certainly more exciting (and succinct) than Pococke’s subsequent accounts. When crossing into the north-west Highlands of Scotland, for example, Defoe pauses to exclaim with wonder on the wildlife, including what he seems to have taken to be the last of the great eagles of Britain:

The mountains are so full of deer, harts, roebucks etc. Here are also a great number of eagles which breed in the woods, and which prey upon the young fawns when they first fall. Some of these eagles are of a mighty large kind, such as are not to be seen again in those parts of the world. Here are also the best hawks of all the kinds for sport which are in the kingdom, and which the nobility and gentry of Scotland make great use of – for not this part of Scotland only, but all the rest of the country abounds with wild-fowl.

Sea eagles were being recorded much more widely than they are today around Britain and Ireland – including around East Anglia and Cornwall, in the uplands of Eryri, and throughout an inland swathe from Peebles in south Scotland down into England as far south as Derbyshire.

But by Defoe’s time, their numbers were declining rapidly – and by the end of the 18th century, sea eagles were essentially extinct across England and Wales. He and other authors wrote wistful accounts about the loss of the species, but like the capercaillie before it, people were powerless to prevent the extinction of these “mighty large” species. The sea eagle, though, has been the subject of several reintroduction projects over the last few decades, and with luck may yet recover much of its former range.

Early signs of ecological protest

Defoe was far from the only literary author interested in the environment at this time. John Taylor, also known as the Water Poet, published entertaining poetic accounts of his trips along the rivers of England – most famously his trip to the mouth of the Thames in a boat made of brown paper

Within mainstream literature, plays written in London often engaged with environmental issues including food, water and timber shortages; air, water and noise pollution; the growing population level; and the decline of game animals.

Among all the accounts I have studied, while it is rare for naturalists to question humans’ right to dominion over nature, the most radical, ecologically sustainable philosophies come from poets of this time. They often wrote poems to trees and animals, and would sometimes even assign nature its own voice.

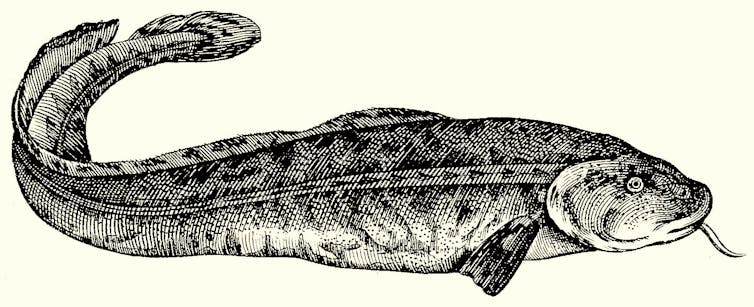

The Powte’s Complaint is a protest ballad probably written in 1619 to bewail the drainage of the Fens around Ely and Wisbech in Cambridgeshire. Attributed in one manuscript to a “Peny” of Wisbech, it is written from the perspective of a burbot, a freshwater species of cod commonly found in the Fens at this time. (This fish is now nationally extinct, but may be soon be reintroduced.)

The ballad summons the “brethren of the water” – probably meaning local people as well as fish and other animals – to fight against the drainage scheme, which sought to create new pasture land:

Come, Brethren of the water, and let us all assemble,

To treat upon this matter, which makes us quake and tremble;

For we shall rue it if ’t be true that Fenns be undertaken,

And where we feed in Fen and Reed, they’ll feed both Beef and Bacon.

According to research by Todd Borlik and Clare Egan, the subject of complaint here was a plan to cut a canal through an area of common land south of Haddenham. This scheme would remove the ability of local people to catch fish, and also to transport their produce and fuel on the water. Protests against the scheme apparently culminated in a demonstration of some 2,000 people who lit bonfires, banged on drums and fired guns all night during a meeting of the Commission of Sewers in 1619.

Within the poem, the alliance of the “brethren of the water” seems to recognise the interdependence of humans and wildlife on each other, and on the environment of the Fens. A comparable example (I would be interested to hear of others from this period) is the Welsh poem Coed Marchan (Marchan Wood), written around 1580 by Robin Clidro, a wandering poet from the Vale of Clwyd in Denbighshire, known for his humorous rhymes.

Clidro’s poem tells the story of a group of red squirrels who go to London to present a petition against the felling of Marchan Wood for charcoal. As with The Powte’s Complaint, the use of the squirrel as narrator is a conceit, and the poem is really a protest against deforestation on behalf of human interests. But again, the author re-imagines the world from the perspective of animals:

Odious and hard is the law, and painful to little squirrels. They go the whole way to London, with their cry and their matron before them. Then on her oath she said, “All Rhuthyn’s woods are ravaged; my house and barn were taken one dark night, and my store of nuts.” The squirrels all are calling for the trees; they fear the dog.

Both poems suggest the existence of empathy for the wildlife being affected by human activity. Indeed, as the era of great industrialisation grows closer, some fascinating accounts emerge of new relations between humans and wildlife. In his Natural History of Stafford-shire (1686), for example, Robert Plot describes being told of:

Very unusual observations concerning scaled, as well as smooth fish … such as their breeding and living in Coal-works. There is an indisputable instance in the drowned Coal-pit-open-works S.W. of Wednesbury, into which Pike, Carp, Tench, Perch, etc. being put for breed, they not only lived but grew and thrived to as large a magnitude as perhaps they would have done any where else, and were to the palate as grateful.

Certainly, the naturalists, travel writers and poets of the 16th to 18th centuries all helped to record a wealth of wildlife throughout Britain and Ireland that is now hard to imagine – even as many also looked forward to its destruction in the quest for more stable, less hungry lives for the growing human population.

Our modern biodiversity crisis could be seen as the culmination of these early accounts, sped up by the arrival of the industrial revolution and the advent of farming on an industrial scale. Yet, in their glimpses of concern and excitement for the natural world, these early-modern accounts also reach across the intervening centuries to show us clear signs of the conservation movement that would emerge in parallel.

For you: more from our Insights series:

To hear about new Insights articles, join the hundreds of thousands of people who value The Conversation’s evidence-based news. Subscribe to our newsletter.