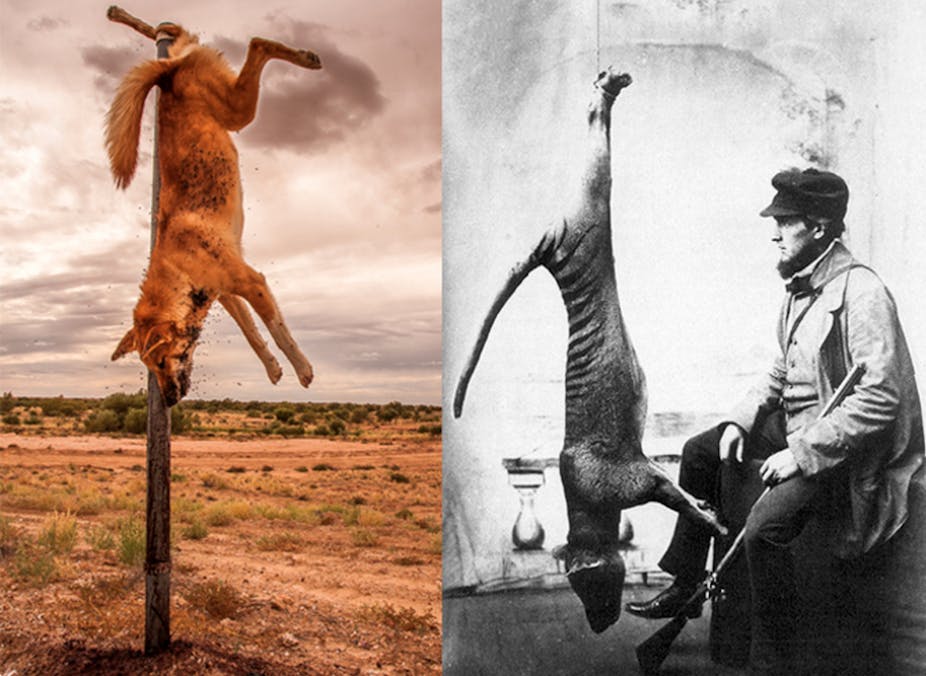

The last Tasmanian tiger died a lonely death in the Hobart Zoo in 1936, just 59 days after new state laws aimed at protecting it from extinction were passed in parliament.

But the warning bells about its likely demise had been pealing for several decades before that protection came too late - and today we’re making many of the same deadly mistakes, only now it’s with dingoes.

Earlier this month the Queensland government announced it would make it easier for farmers to put out poison baits for “wild dogs”. In Victoria, similar measures have already been taken.

Lethal methods of control have lethal consequences. It is time to rethink our approach in how we manage our wild predators.

A deadly history lesson

Commonly known as Tasmanian tigers because of their striped backs, thylacines were hunted due to the species alleged damage they were doing to the sheep industry in the state. However, the thylacine’s actual impact on the industry was likely to have been small.

Instead, the species was made a scapegoat for poor management and the harshness of the Tasmanian environment, as early Europeans struggled implementing foreign farming practises to the new world.

The tiger _[thylacine]… received a very bad character in the Assembly yesterday; in fact, there appeared not to be one redeeming point in this animal. It was described as cowardly, as stealing down on the sheep in the night and want only killing many more than it could eat… All sheep owners in the House agreed that “something should be done,” as it was asserted that the tigers have largely increased of late years._ - The Mercury, October 1886.

More than a century later, and it’s now the dingo in the firing line.

Since 1990, the number of sheep shorn in Queensland has crashed 92 per cent, from over 21 million to less than 2 million. Although there have been rises and falls in the wool price and droughts have come and gone, it’s the dingoes that have been the last straw. - ABC Radio National, May 2013

An ancient predator vs modern farmers

Producing sheep is an incredibly tough business, with droughts, international competition and volatile markets for wool and meat – mostly factors that are well beyond the control of an individual farmer.

Dingoes are seen as one of the few threats to livelihood that producers can fight back against. As a result, the dingo has experienced a severe range contraction since European settlement and there is mounting pressure to remove the dingo from the wild, despite dingoes calling Australia home for 4000 years.

Dingoes are now rare or absent across half of Australia due to intense control measures. While they are more common in other areas, we have seen how species populations can collapse quickly. For example, bounty records from Tasmania showed the thylacine population suddenly crashed in 1904-1910 due to hunting pressure from humans.

Will the dingo’s demise be like that of the thylacine? We simply do not know, but the social conditions and a rapidly changing environment mirror the story of the thylacine.

It’s true that dingoes have an impact on livestock. Estimates from industry-funded reports range from A$40 million to A$60 million, which include damage to livestock and cost of control measures.

And the emotional cost to farmers should not be underestimated. As authors, one of us has sheep farmers in the family, and knows the pride people gain from having a happy and healthy flock.

The choice is whether we want to follow the old colonial attitude of trying to conquer our environment, or find new and cheaper methods to live with our environment.

Dingoes and wild dogs

The issue of how to manage one of the few remaining mammalian top predators in Australia is further complicated by the suggestion that dingoes are not distinct from “wild dogs” due to interbreeding.

In eastern Australia dingo purity is low, but it is still high in many regions, such as central Australia.

But whether you call them dingoes or wild dogs, these predators work as unpaid pest species manager that works around the clock, effectively controlling feral cat and red fox numbers.

Even in eastern Australia, there is evidence that dingoes are fulfilling this role by reducing fox numbers.

Dingoes can also control kangaroo numbers, reducing grazing pressure. Reducing pests and grazing pressure are a win for farmers and conservation alike.

Learning to live with dingoes

As CSIRO researchers suggested a decade ago, we need to get better at dealing with genetically ambiguous animals, such as those that could be classified as dingoes or wild dogs. Instead, they argued that better approach to conservation decisions would involve protecting animals based on their role in the environment, as well as their cultural value.

Traditionally, barrier fences and lethal control (such as poisoning) have been used as methods to reduce livestock losses from dingoes.

However, the costs of removing the dingo as our free pest species manager, and the impact of fences as barriers to other wildlife, need to be taken into account when assessing the true cost of maintaining these approaches.

Alternatives to lethal control do exist. Guardian dogs can protect stock from dog attack and have a return on investment between one to three years. Such cost-effective strategies can allow both the dingo and grazing to co-exist.

Over thousands of years, dingoes have played a functional role in the Australian landscape and can provide benefits for farmers, traditional Indigenous owners and to the conservation of native wildlife.

It is time to learn how to live with the dingo. If not, we risk eventually driving dingoes out of the wild and into lonely zoo enclosures, just like the thylacine.