Until recently, the international climate negotiation process revolved strictly around high-level conversations between nation states. However, this is changing in a way that may lead us to rethink the structure of global climate talks.

In particular, nonstate actors, such as businesses and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), are becoming increasingly influential players, transforming the overall conversation – something we witnessed firsthand at the COP22 summit on climate change in Marrakech, Morocco this month.

This shift has the potential to not only bring new voices into discussions over how the world addresses climate change, but also create more effective forums for taking action.

Disengaged US president-elect

COP22 wasn’t the first time climate talks have been held in Marrakech. The city hosted the same forum in 2001 at a time when George W. Bush had recently been elected president. He promptly removed the U.S. from the global climate treaty known as the Kyoto Protocol. That decision cast a pall over those earlier talks, but that pales in comparison to the effect of Trump winning the U.S. election.

With his administration preparing to take power, there is every expectation that the United States will disengage. President-elect Trump has explicitly indicated he will end the U.S. involvement in the Paris Agreement and the climate negotiation process more generally, although some expect the disengagement may not be quite as severe.

How and whether the U.S. officially pulls out of the Paris Agreement or otherwise removes itself from the formal process is still unclear (there are at least three possible scenarios). But one thing is certain: The U.S. can no longer be expected to be as active a player as it was under the Obama administration.

This means a different form of engagement is needed for continued progress in addressing climate change. Fortunately, changes in the negotiation environment are taking place.

Stepped-up role of nonstate actors at Marrakech

For over two decades, international climate talks held under the auspices of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) were focused on coming to a long-term, comprehensive global agreement on climate change.

This was achieved in 2015 with the Paris Agreement, which puts forth a comprehensive architecture designed for the long term. It requires all parties to submit voluntary “Nationally Determined Contributions” (NDCs) to reduce their national greenhouse gas emissions. These pledges are designed to assess how far we have to go toward hitting global climate mitigation and adaptation targets, and how far individual states have gone toward doing their part. Over time, countries are supposed to set more ambitious targets.

The key challenge in Marrakech was to take steps to operationalize the Paris Agreement, and here we saw greater involvement of nonstate actors.

As Secretary John Kerry pointed out during his address in Marrakech, market pressures and low-carbon initiatives, more than states, will play an increasingly central role. Economic agents remain important, not merely for direct financial aid and engagement with the market, but also for insurance and other mechanisms of support.

Substate actors can be cities, states and provinces as well as economic institutions, such as development banks. Other groups include research bodies, such as academic institutions, and NGOs.

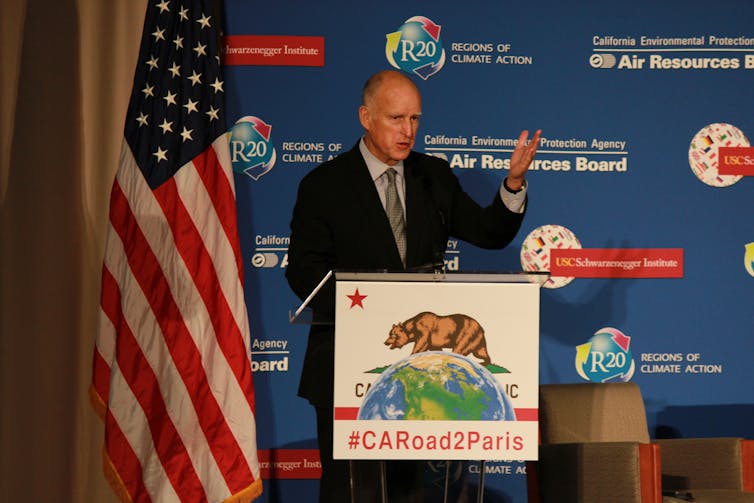

This stepped-up role for nonstate actors was particularly notable at COP22 in Marrakech. For example, representatives from California reaffirmed their commitment to reduce the state’s emissions regardless of federal policies.

The interaction between states, and between states and nonstate actors, has the potential for being increasingly collaborative and decreasingly confrontational. For example, the development of a program engaging High Level Champions for Climate Action, begun in Paris, came to fruition in Marrakech. This program gathered an unprecedented network of nonstate actors and put them in dialogue. These dialogues, with the intent of increasing ambition from all parties, demonstrated a remarkable shift toward collaboration.

We saw these dialogues taking place in Marrakech. One example is the financial sector’s engagement in the discussion of how rich countries provide money to poor countries to adapt to the effects of climate change. In one striking example, the World Bank voiced its engagement with the distinctive perspectives of indigenous peoples for sustainable development.

Moreover, as part of a concerted effort to bring both public and private sectors to bear on climate change, a platform was developed to showcase collaborative efforts, and motivate new partnerships and opportunities.

As Manuel Pulgar-Vidal noted in a side event to the talks in Marrakech, there used to be considerable tension and adversity between state and nonstate actors in previous years, most notably at COP19 in Warsaw. The Lima-Paris Action Agenda was launched to overcome this tension and catalyze greater collaboration. In Marrakech, we have seen a much less confrontational atmosphere, and a corresponding change in the political environment.

Three outcomes

This evolving landscape has implications for how international collaborations to address climate change move forward, even with waning official U.S. engagement.

First, the addition of nonstate actors brings interests not typically reflected into the policy arena. For example, subnational bodies such as the state of California can bring in new perspectives on climate action initiatives that might not otherwise be available. Or, in another example, the inclusion of indigenous voices can bring in a set of interests that have not been sufficiently represented.

A broader array of resources, perspectives and expertise provides a more comprehensive approach to policy. Certainly, this diversity of perspectives brings new challenges in coordinating various groups and their interests, but it also opens new opportunities for cooperation.

Second, by including interests that are at least one step removed from formal political agents, the ongoing landscape will be separated from the four- or five-year time span of typical state-level elections. As one of us (Boran) has argued previously, multilateral engagement that promotes a diversity of perspectives, expertise and know-how can become a strength of long-term climate policy. This, it may be hoped, provides a better chance of developing and implementing approaches to climate mitigation, adaptation, and financial support on longer time scales.

Third, by bringing in nonstate actors there is greater potential for bilateral and multilateral engagement between drivers of climate action with overlapping interests. More agents in conversation open up new channels for collaboration, which is a better approach for the complex challenges presented by climate change.

Hope beyond the state

Clearly, the openness we saw in Marrakech to engage an increasingly wide range of actors in the global climate effort cannot be a substitute for the work nations have to do. But it may well prove at least as consequential in the long run as formal U.S. political engagement. And it may provide a new direction for the future of international collaboration and multilateralism. That should give us hope for progress on climate change.