What do silver, silicon and gallium have in common? These expensive raw materials are essential components of our various solar energy technologies. What about neodymium, praseodymium and dysprosium? These rare earth metals are used to build the powerful magnets in wind turbines.

Keeping our planet liveable requires accelerated clean energy transitions by governments — global carbon emissions must halve by 2030 and achieve net-zero by 2050.

But a more ambitious clean energy transition requires more of the metals and minerals used to build clean energy technologies. As the global energy sector shifts from fossil fuels to clean energy, the demand of precious metals — known as critical minerals — is increasing.

Read more: Critical minerals are vital for renewable energy. We must learn to mine them responsibly

A striking example is lithium, a metal used in electric vehicle batteries. Between 2018 and 2022, the demand for lithium increased by 25 per cent per year. Under a net-zero scenario, lithium demand by 2040 could be over 40 times what it was in 2020.

Supply and demand

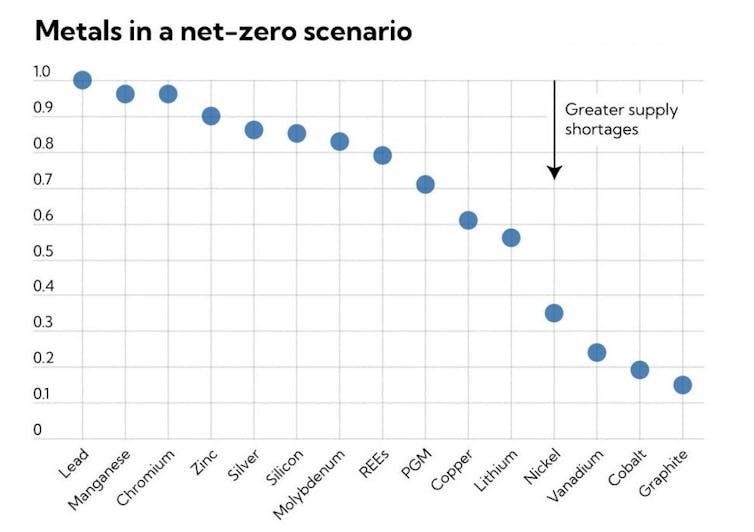

The current challenge lies in a supply and demand mismatch. The projected demand for critical minerals exceeds the available supply. Basic principles of economics dictate higher prices for these minerals.

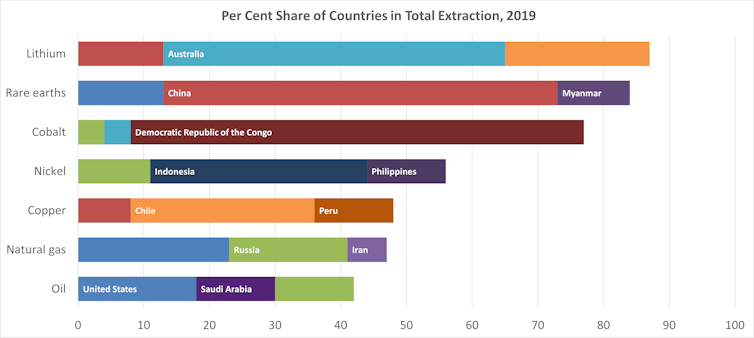

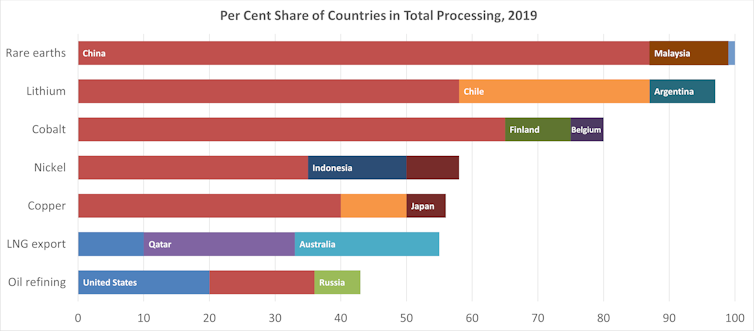

In addition, critical minerals have a geographically concentrated supply. These metals are only extracted from a handful of countries and are overwhelmingly processed in China.

China, for example, extracts 60 per cent and processes 90 per cent of all rare earth elements. In comparison, the top oil-producing country — the United States — accounts for only 18 per cent of the extraction and 20 per cent of the processing of the whole industry.

The geographical concentration may result in additional supply constraints. Indonesia, the world’s first nickel producer, has progressively banned the export of nickel ore overseas in an attempt to strengthen domestic processing.

The lack of geographical diversity in supply can increase price volatility. Lithium prices rose more than 400 per cent in 2022, before dropping again by 65 per cent in 2023. Copper prices soared in Peru following social unrest and mine blockades.

China, which controls 98 per cent of the gallium supply, created a 40 per cent spike in 2023 on gallium prices by setting severe restriction on exports due to “national security reasons.”

If supply constraints continue, the prices of critical minerals could become too high. Installing clean energy could become too expensive, and governments may find it hard to reach their clean energy targets.

The demand and supply balance must be restored by one of two ways: either by decreasing the demand for critical materials or increasing their supply.

Restoring balance

The most obvious way to restore the balance between supply and demand — more mining — is tricky. Mining is environmentally destructive and damages ecosystems and communities. Plans for opening new mines in France, Serbia and Portugal have seen massive social opposition, leaving their future uncertain.

Opening a new mine can take more than 15 years on average, so projects started today might arrive too late. While some capacity can be built quicker by reopening old mines, and some projects are already underway, supply imbalances are expected to be inevitable by 2030.

Beyond mining, two alternative practical approaches exist. The first is to reduce the demand for critical minerals by clean energy technologies. With innovation and research and development, clean energy products can be redesigned to use less material in each generation.

The silver content in solar cells dropped by 80 per cent in one decade. Likewise, the cathodes in new electric vehicle batteries contain up to six times less cobalt than older models.

The second alternative is to increase the supply of critical minerals by recovering them from older and used clean technology products via advanced recycling. Decommissioned solar panels might no longer produce energy but can be a valuable source of silver or silicon.

Our past research has shown that discarded solar panels could outweigh new installations by the next decade as installers seek to replace older panels with newer, more efficient ones.

By recovering critical minerals from this waste in a process known as urban mining, we could cover the demand for the materials needed for future energy installations.

Recycling is the way forward

Our recent research with our colleague Luk Van Wassenhove compares the economic consequences of these two alternative approaches. If the scarcity of critical minerals is not extreme, reducing the critical material content of clean energy products would be the way to go.

However, unintended consequences can be expected akin to the rebound effect or Jevon’s paradox: by improving the efficiency of usage of critical minerals, producers can end up consuming more of it.

As clean energy products use less critical material, their improved profitability could increase production even more. As a result, decreasing the material usage per product won’t necessarily lead to a decrease in critical material demand overall.

In contrast, our research suggests that recycling decommissioned products is not subject to such a rebound effect. A steady stream of recycled materials from end-of-life products protects producers from volatile commodity prices and better facilitates the critical energy transition.

Setting up a recycling ecosystem requires greater effort than marginally changing a product’s design. Firms need a cost-efficient reverse logistics system, recycling plants and infrastructure to get enough end-of-use products back and to process them. Sizeable initial capital investments will take time to recover and require firms and policymakers to adopt a long-term mindset.

But there’s room for optimism. The start-up ROSI Solar opened its first recycling plant in 2023, making France a pioneer in recovering high-purity silicon, silver and copper from end-of-use solar panels.

Likewise, the U.S.-based SOLARCYCLE can recycle 95 per cent of valuable materials in solar panels. Many electric vehicle makers, like Tesla, Renault and Nissan, have started projects to recycle batteries and ensure a riskless cobalt, nickel and lithium supply. Recycling may indeed be the path to affordable clean energy.