Two 2017 films, Christopher Nolan’s Dunkirk and Joe Wright’s Darkest Hour, once again take viewers back to a key period in British and European history. Barely 18 months after the Brexit referendum, and at a time when the British are asking themselves some uncomfortable questions about their future relationship with the European Union, these two films have raised important questions about the country’s fundamental – European or non-European – identity. The weight of history, in particular the history of 1940, and the ways in which it is being represented in the media and elsewhere are essential elements in the debate over Brexit, fuelling the strong feelings on both sides.

In fact, these two films are only the latest examples of a genre that goes back to World War II itself and that praise the courage of the British at this most acute period of national crisis, a period that Winston Churchill famously referred to as the country’s “finest hour”. Wartime propaganda films such as Mrs. Miniver directed by William Wyler (1942) or post-war productions like Battle of Britain by Guy Hamilton (1969) established a certain idea of the war in Britain’s collective imagination. Music from Michael Anderson’s 1955 film The Dam Busters, with its associated imagery, remains one of the favourite tunes of British football fans.

In January 2018, Germany’s ambassador in London asserted that many people in Britain pay excessive attention to the past, in particular World War II, while focussing far less than they should on the present or the future. As a result, for many Britons, the overriding image of Germany and of the other European nations continues to be conditioned by past events that are becoming increasingly distant in time but which show few signs of losing their influence.

Brexit, British victories and defeats

So how should we interpret the images of Britain that are being conveyed by these films and what has their impact on the Brexit debate been? Quite rightly, both films have recognised the complexity of this history. Neither Dunkirk nor Darkest Hour attempt to mask the fact that for Britain the events of May-June 1940 were a catastrophe. The hesitations at the heart of the British government and the establishment, and even the temptation to sign a peace agreement with Hitler, are fully recognised in the accounts they give.

Nevertheless, it is the idea of Britain as valiant, heroic, determined in its resistance and its “Dunkirk spirit”, exemplified by Churchill’s famous “We shall never surrender!”, that underlies most popular visions of these crucial weeks in the summer of 1940. In this respect Dunkirk and Darkest Hour continue to evoke the history of 1940 in similar ways to previous generations of film productions.

For supporters of Brexit, above all those demanding a hard Brexit, the essential lesson to be drawn from this history is that Britain is, both in its fundamental nature and in its national interests, different from – and for some superior to – the other European countries. This sense of difference and of separation takes various forms.

A long history of difference

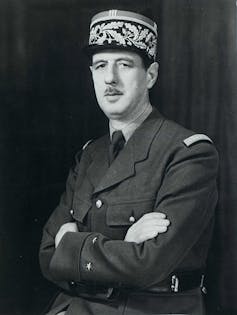

First, there is the geographical aspect. Charles de Gaulle liked to point out that “England is an island” and never missed an opportunity to underline this obvious fact in all his discussions of the relationship between Britain and the Continent. Dunkirk and Darkest Hour reinforce this same idea, frequently using the white cliffs of Dover and the sea as a backdrop to some of their most memorable scenes. They’re in Shakespeare’s Richard II as well, serving “as a moat defensive to a house, against the envy of less happier lands”. In the films, as in the past, the danger comes from across the Channel, from the continent. Britain is alone, an isolated fortress, threatened on all sides, but standing firm. Today’s Brexiteers are inclined to express similarly jingoistic sentiments.

Boris Johnson, a key figure among the Brexiteers and biographer of Churchill, has frequently taken inspiration from the history of 1940. In an attempt to take up the mantle of his hero, Johnson has waged a combat against what he considers to be a new form of the continental menace, even going so far as to argue that the objective of the European Union, led by a renewed and increasingly confident Germany, is not far removed from that previously pursued by Nazi Germany: the establishment of a European super-state.

Faced with this danger, Johnson called on his compatriots to once again assume the role of “heroes of Europe” just as their predecessors had done in 1940 and to “liberate” the country from the EU. Nigel Farage meanwhile has spoken of the risk of the country being reduced to some sort of “Vichy Britain” in the event of a “soft” Brexit in which the UK remains inside the European single market and the customs union.

In all of this discourse, the links to the past, and especially to the World War II, are clear: Germany is still regarded as a threat and the other Europeans, above all France, are seen as being all too willing to acquiesce in this new European order. Those in Britain who refuse to accept the outcome of the referendum, or who favour a soft Brexit, are condemned as heirs of the appeasers of the 1930s. The most excessive arguments of this sort have been widely condemned across the political spectrum, although without always being contradicted. In many ways they reflect an opinion that is deeply-rooted in Britain and which has often been voiced in the media which for the most part has long been won over to the cause of Brexit.

An old and on-going European debate

This tendency to use history in the European debate is nothing new. At the beginning of the 1960s, when the Macmillan government was launching Britain’s first attempt to enter the then European Common Market, the ex-Prime Minister Clement Attlee expressed his outright hostility to the whole idea. Looking back on the record of the war, he asked why the country should want to be associated with the “Six” given that only a few years before Britain had “spent a lot of blood and treasure… rescuing four of them from the other two.”

In similar fashion, Hugh Gaitskell, the leader of the Labour Party, famously declared in 1962 that entering the Common Market would mean “the end of a thousand years of history” and that while Europe had had “a great and glorious civilisation”, and could point to Goethe, Leonardo, Voltaire and Picasso, it had also had its “evil features” in the shape of Hitler and Mussolini. It was, he ominously warned, still far too soon to say which of these “two faces” of Europe would ultimately triumph.

The following year, the veto imposed on the British application by General de Gaulle that ended British hopes of entering the Common Market brought an angry reaction from Macmillan, who saw this as a lack of recognition on the part of the French leader for the assistance Britain had given him during the War. He sought solace in the lessons of Britain’s previous relations with Europe. The British, he said, had resisted such tyrants as Philip of Spain, Louis XIV, Napoleon, the Kaiser and Hitler, and they would be quite capable of doing the same again now that they were facing a similar danger of a Europe dominated by de Gaulle’s France. In reality these attempts to find some comfort in Britain’s glorious past was a vain attempt to disguise his own impotence and that of his country.

Britain’s place in the world?

But should we regard the events of May-June 1940 as necessarily a distancing of Britain from the Continent or Churchill as a precursor of today’s Brexiteers? Can we see in the history being told in the films Dunkirk and Darkest Hour some sort of justification for, or explanation of, the rising tide of Euroscepticism, or Europhobia, that led to the result of the 2016 referendum? Or should we, on the contrary, recognise that Britain, by choosing to continue to fight on in 1940 and not to abandon the other Europeans, was never so European as in May-June 1940? In this case we need to see the story being told in these two films as proof of an engagement both for Europe and alongside the other Europeans.

As Churchill recognised in 1940, and which is clearly shown in Darkest Hour but which so few of the Brexiteers now appear willing to accept, Britain can never withdraw into some sort of island sanctuary, “leaving Europe” to find refuge elsewhere in the world – how? The inclination of so many Brexiteers to look back 75 years into the past and to refuse to accept that the power Britain enjoyed at that time has long since disappeared has seriously harmed the present debate and done nothing to address the real issues facing the country today.

In one of his most famous speeches to the House of Commons in June 1940, re-created in the final scene of Darkest Hour, Churchill promised to continue the fight until victory was finally won thanks to the support of the British Empire, the Royal Navy and the New World. Today, however, the Empire has long since disappeared, and even the relations with the old Dominions such as Australia, Canada and New Zealand are far from providing Britain with the help that the country needs. The backing of the United States, uncertain in 1940, is once again in doubt given its present administration. The Royal Navy is a shadow of its former self and it seems most unlikely that the “little ships” who saved so many British and allied soldiers from the Dunkirk beaches in 1940 could do the same again today.

Click here for a list of references to Richard Davis’ articles, including “Britain in Europe: Some Origins of Britain’s Post-War Ambivalence”, published in “Britain and Europe: ambivalence et pragmatisme”, edited by Claire Sanderson, Cahiers Charles V, December 2006, No. L. 41, pp. 15-38.