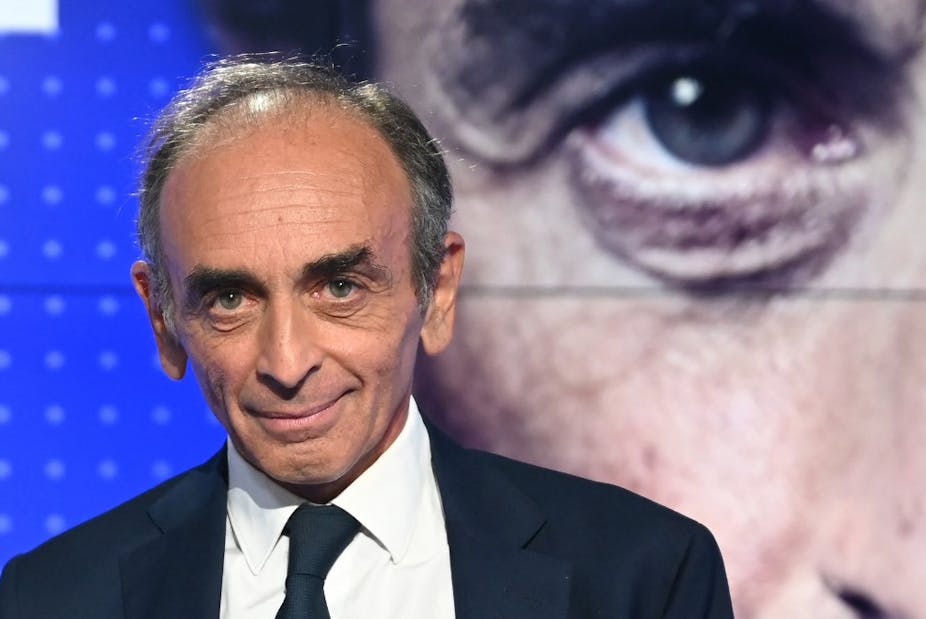

In October 2021, the far-right presidential candidate Éric Zemmour was on the heels of Marine Le Pen, polling 16%. However, in the latest survey by BFMTV, dated 5 April, his support has nearly fallen by half, to just 9%.

What changed everything was Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. A backer of the traditional values espoused by the Kremlin, Zemmour’s long-standing call for closer diplomatic ties with Moscow and criticisms of NATO have backfired. Having committed a first political blunder in December by “betting Russia would not invade Ukraine,” the candidate haemorrhaged further support when he recently rejected the possibility of hosting Ukrainian refugees. Meanwhile, Marine Le Pen has also managed to overtake him as the champion for living standards, at a time when the economic fallout from the war continues to skim off Zemmour’s natural supporters.

Regardless of his position, the candidate will have left a deep mark on the presidential campaign by shifting public discourse further to the right. A few days ahead of the first round of the elections, political scientist Alain Policar walks us through his most popular – and controversial - ideas.

Lire cet article en français: Éric Zemmour: une histoire française

The ‘Great Replacement’ theory

Throughout the campaign, Zemmour has openly promoted the “Great Replacement” theory – a racist belief, popular on the far-right in Europe, the US and the UK, that white people will soon be “replaced” by non-white, non-European immigrants.

The head of Reconquête, who has been convicted by the French courts twice for inciting racial hatred, would have us believe that France’s greatness is built upon its position at the top of a “hierarchy of cultures”. This position turns a blind eye to the horrors of French colonial racism, considering it a necessary price for offering colonised people their moral enlightenment.

Assimilation and separatism

In Zemmour’s view, French life and French values are under threat from Islam. He argues that France is contaminated by “separatism”.

“Separatism” is a loaded term in France. It was once used to describe anti-colonial struggles, particularly those in Algeria and has been the standard accusation thrown at Jewish people since antiquity, and forms the basis of much modern anti-Semitism. But it is also current government policy to root out “separatism” through a new law promoting “respect for the principles of the Republic”.

Zemmour is also an ardent supporter of assimilation of migrants to France. His endorsement of assimilation should not be surprising, particularly when we recall that this word was once used to justify the race-based politics evident in the privileges enjoyed by French colonists, which turned them into a quasi-aristocracy; a race apart.

In fact, American historian Tyler Stovall observed that colonists were more inclined to call themselves “white” or “European” than French. He writes:

“It was in the colonies that understandings of the French national idea first became confused with the racial idea of whiteness.”

Yet upholding assimilationism in Zemmour’s view would also imply the non-assimilation of certain groups. He regularly argues, for example, that Islam is not compatible with the Republic – the opposite of assimilationist politics.

This is also an idea with deep roots – it should be remembered that to obtain French citizenship in 1958, Algerian Muslim women were required to remove their headscarves during inauguration ceremonies. What better way to illustrate that you had to stop being a Muslim woman to become a French one?

False universalism

Zemmour’s pronouncements may be incendiary, but through them we can see that the old idea of a French nation defined in racial terms has had a lasting influence on contemporary debate.

One such idea is that of “universalism”, which holds that the national characteristic of being French supersedes any other identity an individual may have. But if immigrants are asked to defer to French traditions based on an assumption that such traditions are inherently universal, universalism becomes not a form of humanism that embraces diversity, but rather a nationalistic symbol.

This is how Achille Mbembe described the concept in a 2005 article:

“Having long upheld the ‘republican model’ as the perfect vehicle for inclusion and the emergence of individuality, we have ultimately turned the Republic into an imaginary institution, and underestimated its original capacity for brutality, discrimination and exclusion.”

A harsh judgement, perhaps, but French history (long before the establishment of the Republic) attests to this racialised dimension. When it uses national identity as the guiding light of the republican cause, universalism has been seriously misled, to the point of forfeiting all substance.

It is worth noting that this version of universalism can appear in other guises, particularly in anti-cosmopolitanism, which slanders society’s incorrigible utopians and blindsided bleeding hearts. This is precisely the tone adopted by Éric Zemmour.

One might even hypothesise that hiding behind this false universalism is a hatred of the universal, exemplified in the famous quote by Joseph de Maistre in his Considerations on France (1796):

“In my life I have seen Frenchmen, Italians, Russians, and so on. I even know, thanks to Montesquieu, that one can be Persian. But as for man, I declare I’ve never encountered him.”

In much the same way, Zemmour presents us with a fragmented world that offends his own obsession with purity – his simultaneous hatred of intermingling and a fear of sameness.

Three years ago, my colleague and I wrote an article about Zemmour’s place in the public arena in France, and how we should resist his impoverished, extremist rhetoric. While Zemmour is likely to have his campaign come to an early end, many of his ideas continue to live through Marine Le Pen. More provocative than his rival, the former journalist may have unwittingly given her the means to make it to the second round herself – and possibly to Elysee Palace.