Malaysian prime minister Najib Razak has confirmed that Malaysia Airlines flight MH370 crashed in the southern Indian Ocean, with no survivors. In a press conference, Razak said new information proved “beyond reasonable doubt” that the plane was lost.

The new data came from the UK Air Accidents Investigation Branch and private company Inmarsat. The plane disappeared on March 8 en route from Kuala Lumpur to Beijing.

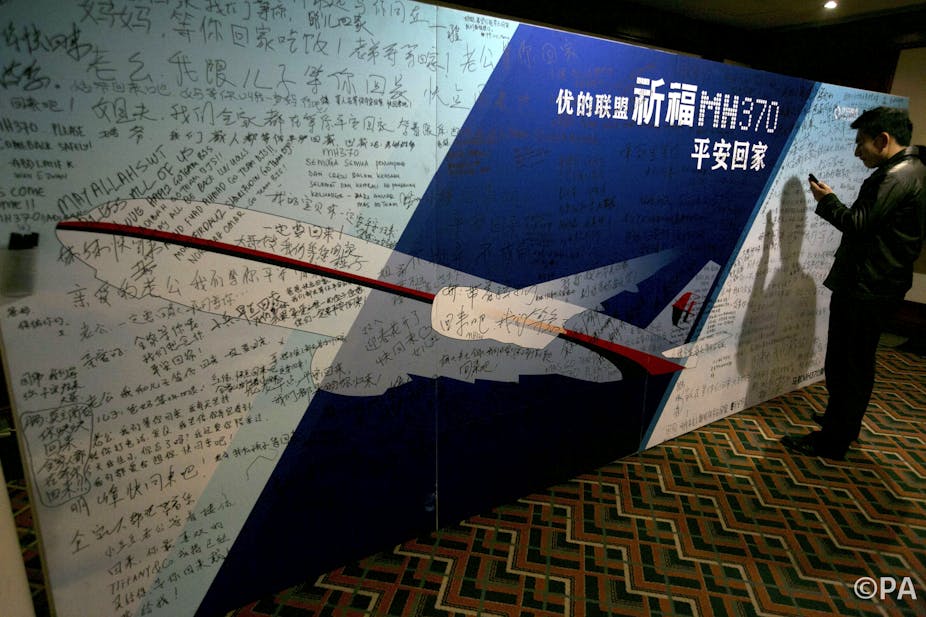

Relatives of the passengers were notified of the news by text message.

The Conversation is seeking response from academic experts in various fields to make sense of the conclusion to this tragedy.

How do you recover plane debris from the bottom of the ocean?

Thomas Furey, Section Manager, Advanced Mapping Services at the Marine Institute

Recovering debris from the deep ocean is a challenging task. The process involves locating the debris using advanced mapping technologies, which is often the hardest part, particularly in deep water or large search areas.

There are a lot of uncertainties in the case of MH370. Even if we had the exact location where the plane went down, the area of seabed on which which the debris could have eventually settled could be very large. Many factors are at play – the angle at which the debris sinks to the bottom, the ocean currents in that area, and the size of the debris. Some commercial companies and government organisations have the modelling capabilities to broadly model the extent of the search area on the seabed in which the debris could end up, but only based on a known location at which a plane hit the sea surface.

Once the approximate area is determined, the mapping procedure can begin. This type of work is typically carried out by vessels that can cost anywhere from US$30,000 to US$50,000 per day. In the case of MH370, the southern Indian Ocean can be as deep as 5km, which means a typical hi-tech vessel might be able to map an area 15km by 20km wide per hour.

The mapping is done by sending multiple soundwaves from the vessel to the seafloor. The time difference between when it is sent out and when the reflected signal is returned to the vessel allows the crew to create a map of the seabed topography, with some information also ascertainable on seabed hardness. As the depth of the ocean increases, the resolution of the surface that can be mapped decreases. This is why finding debris smaller than 50m wide is extremely challenging in these water depths.

Once located, debris can be recovered using remote-controlled equipment that is dropped to the sea floor. A vessel with a remotely operated vehicle would typically be deployed with onboard cameras and robotic arms to investigate and/or recover debris.

In the case of the MH370, if located, there is a chance that whatever debris reaches the floor may remain well-preserved, albeit potentially over a very extensive area of the seabed. Locating the debris is further dependent on whether the seabed is hard, or very soft. The latter could result in partial burial in the upper sediment layers. Factors that will impact the status of the debris include the high pressure at such depths, and chemical decomposition over time as debris is exposed to salt water.

Reader question: how do you go about locating the black box signal?

Matthew Greaves, Head of the Safety and Accident Investigation Centre, Cranfield University

The black boxes (the Flight Data Recorder and the Cockpit Voice Recorder) have Underwater Locator Beacons (ULBs) attached. When immersed in water, these start emitting a pulse, once a second, at 37.5 kHz. How far this can travel depends on a range of things including sea state, temperature gradients, and terrain.

The signal is detected using a hydrophone which is essentially an underwater microphone. By measuring from different positions relative to the ULB, the signal from the hydrophone can indicate direction and strength to try and triangulate the ULB location.

Typical detection ranges are a few kilometres, which of course includes the depth of the ocean (about 3,000m in the area they’re searching) and so they may need to use a towed array (hydrophones in a long cable) which can be towed behind a boat and submerged in the water to shorten the distance between the ULB and the receiving hydrophone.

Comparing this to the current 500,000 square nautical mile search area (down from the original 2.2 million square nautical miles), it’s clear the investigators need a much better idea of where the aircraft crashed before starting the underwater search.This is why the BEA are saying it’s too soon to bring in submarines which have sonar arrays that may be able to detect the ULBs.

The ULBs have a finite life of 30 days due to battery life. After the Air France 447 accident, the requirement has changed to 90 days but this needs to be implemented by 2018. The manufacturer has started shipping 90 day ULBs as standard but it’s unclear whether this ULB will last for 30 days or 90 days.

Reader question: how was the Inmarsat satellite data used to identify the route?

David Stupples, Professor of Electrical and Electronic Engineering, City University

Soon after the last voice communication was made at 0107 hours by one of the pilots of Malaysian Airlines Flight MH370, the Very High Frequency radio, Aircraft Communication Addressing and Reporting System (ACARS) and the the aircraft’s secondary surveillance transponder appeared to have been switched off or disabled. However, the aircraft’s satellite communications system remained active – perhaps the flight deck crew still required navigation data?

To remain connected to the Inmarsat communications satellite, a geostationary satellite over the Indian Ocean, the aircraft’s system sends a registration message hourly which is acknowledged by the satellite. Using timing information Inmarsat scientists calculated that the aircraft either flew in Northern or Southern arc from its last reported position over the strait of Malacca.

Evidence from Thai and Burmese primary ground radars confirmed that the aircraft did not fly in the Northern arc. Inmarsat then used theories from the Doppler effect to analyse the seven registration “handshakes” made between the aircraft and the satellite. The scientists were then able to plot the aircraft’s movement along the southern arc to approximately where hitherto unidentified ocean debris has been located. Although this evidence in not conclusive, it is compellingly strong.

Reader question: has media coverage been over the top?

Professor Karin Wahl-Jorgensen, Director, Research Development and Environment, Cardiff School of Journalism

The extent to which particular disasters become prominent in the news is determined by a complex range of factors. The disappearance of flight MH370 was, by any measure, a spectacular news story. It had drama, it had mystery, and it resonated with popular culture discourses of aeroplane disappearances, as embodied in the popular television series, Lost.

It was also an ongoing and unresolved story – for journalists, a gift that keeps on giving. It was the kind of event which invited other resonant story lines, including ones of terrorism and conspiracy. Because the search for the missing aeroplane quickly came to involve a huge number of actors and countries, it also became a major international news story with reverberations across a globalised media landscape.

One of the factors shaping coverage of disasters – whether “man-made” or “natural” – is what’s called a “calculus of death” at work, based on crude body counts as well as proximities of geography, culture and economics. Plane crashes are typically highly newsworthy, because they involve a larger number of deaths as the result of one discrete incident, as opposed to the ultimately far more significant number of deaths caused by the slow, but constant trickle of automobile accidents.

Malaysia Airlines response

Morgen Witzel, Fellow, Centre for Leadership Studies, University of Exeter

Malaysia Airlines’ decision to use text messages to inform families of passengers on MH370 their loved ones were dead must go down as one of the most crass management decisions of all time.

Malaysia Airlines has signally failed in its duty of care to the families of those passengers. In fairness, hard information in this case has been difficult to come by, and the authorities in both Malaysia and China have been baffled by the aircraft’s disappearance. But that is not an excuse. The passengers on MH370 were the airline’s responsibility. The families are entitled to support. Senior executives of the airline should be in Beijing and Kuala Lumpur talking directly to them, promising assistance, promising to hold their own inquiry to ensure such an event never happens again.

This is not just a humanitarian issue; it is also a matter of good business. The dilatory and – to use the word again – crass response to the deaths of its passengers has done incalculable damage to Malaysian Airlines’ reputation and its brand. Why should anyone, passengers, employees, investors, trust this brand again?

Malaysia’s response

Adam Tyson, Lecturer in Southeast Asian Politics, University of Leeds

The Malaysian authorities responsible for handling the MH370 crisis were unprepared for the level of international scrutiny that began on 8 March. The mishandled case can be explained in part by the prevailing political system in Malaysia. The ruling party is publicly accountable but certainly enjoys the strong backing of national newspapers such as Utusan Melayu and television networks such as TV3, creating a layer of insulation from scrutiny.

Senior officials tend to operate in a highly controlled hierarchical environment. Malaysian officials of rank do not deal well with criticism, and often accuse domestic activists and critics of conspiratorial motives – an effective diversionary tactic in most cases.

Officials on the frontline of the extraordinary MH370 case were subjected to relentless questioning. There was no script to follow, and unlike other recent international controversies (the Anwar Ibrahim trials), no usual suspects to blame. Chinese journalists and investigators were particularly vigilant, and the growing microblog community caused further confusion and anger by rapidly spreading rumours.

There was no hiding place for aristocrats such as Datuk Azharuddin, the Director General of Civil Aviation, or Dato’ Seri Hishamuddin, the transport minister. It was only a matter of time before Malaysian commentators set aside their grief and channelled their anger toward Hishamuddin, who implausibly has double ministerial duties (transport as well as defence) and is the cousin of current Prime Minister Najib Razak.

Searching the southern Indian Ocean

Chris Hughes, Professor of Sea Level Science at the University of Liverpool

It would be hard to choose a more complicated region of the ocean to be searching for debris. The search area west of Australia lies just on the northern flank of the Antarctic Circumpolar Current, a huge ocean current encircling Antarctica which is in many ways similar to the atmospheric jet stream, or a series of jet streams.

It is now 16 days since flight MH370 was lost. In that time, debris could have drifted by several hundred miles from where, it is presumed, the plane hit the water, and the patch of debris could have spread by a substantial fraction of that distance.

So, even once debris has been found and confirmed to be from the plane, finding any sunken remains will still be a big challenge. The ocean in that region is about 3,500 to 4,000 metres deep, and finding sunken wreckage will involve combing a vast area with advanced sonar imaging technology.

Then there is the challenge of reaching it. Only specialised equipment can operate at the pressures of more than 350 atmospheres which are involved.

Recovering the black box

Yijun Yu, Senior Lecturer, Department of Computing and Communications, and Andrew Smith, Lecturer in Cisco Networking, Open University

The first step for the MH370 mission is to find the black box. The device is actually more often orange or yellow in colour so that it can be found more easily following a plane crash but it is still no mean feat to locate one. It took around two years to find the black boxes from Air France flight 447, which crashed in the Atlantic in 2009. The search for MH370 has already proved difficult and ocean currents may carry the device and other parts of the wreckage on an unpredictable journey.

Then, once the black box is found, we can’t be certain that it will yield information. While the devices are designed to tolerate immersion in water, high velocity impact and damage, they are not indestructible. Occasionally data has to be collected from their remains which means there has to be a scientific and forensic process of analysis. Success on this front will depend on how the data is stored as well as the battery life of the black box.

Technological issues aside, once the recordings have been recovered from the black box, investigators will have to decide if what was said by the pilots in the final moments of the flight can be believed. It can really only be treated as one piece of the puzzle.

The opinions of the pilot and co-pilot, no matter how experienced they are, can only be based on what they see and believe as they handle a high-pressure situation. This may not entirely reflect what the actual aviation issue may have been unless there is other data to back it up.

Families dealing with grief

Peter Kinderman, Head of the Institute of Psychology, University of Liverpool

The argument for sending everyone a text message is that you don’t want the news to drip out in an uncoordinated way so you can see why they’d say, “Let’s have a single message.”

It sounds brutal, it sounds like a bad way to do things and it could seem ill-advised, but one of the things that is really bad for people is to have uncontrolled rumours. So I can see why you’d want to give this message very clearly and in a way you can literally take away. But it’s important that the families are taken aside, told what they need to know and have it followed up with written information.

But there are other limitations, apart from the image that this conveys. Anyone who receives that text message would immediately have their questions. If you’re sending someone a text message, every single person will have a different question: When did you decide? Have you seen bodies? Is this based on statistical probability? Do you know why? All of the questions will come out and those are not easy to respond to via text message.

The first things the families need now is information – they need information more than anything else. Authorities need to tell them as much as they know, as clearly as they can.

The second thing they need is to have a sense of community and shared support for each other. When people go through shared tragedies, those tragedies are somewhat easier to bear if you’re part of a community. At this stage, I wouldn’t necessarily try to offer them therapy or counselling, I’d try to offer them facts and try to build a sense of community.

We mustn’t second guess people’s psychological reactions. As a psychologist I wouldn’t try to interpret those reactions. Whatever is happening should be considered normal.

What can the media do? They shouldn’t use grief as spectator sport. I know it’s very attractive, but you should leave them alone. Please don’t think the media can do something helpful for these people. Don’t take photos when somebody is doing something slightly unusual like rocking or praying or getting angry; that’s what people do. They’re not odd, they’re not strange and they’re not particularly interesting. Don’t judge them, and leave them alone. All shades of human emotional response are normal and natural.

More to come.

Do you have more questions about MH370? Leave them in the comments below and we’ll try to find experts to answer them.