Political scandals, the perennial product of the grinding gears of greed and governance, proliferate in the age of digital media, the 24-hours news cycle and anti-corruption bodies with wide powers.

Constant tonal inspiration is drawn from the tracking of the 1972 break-in at the Democratic National Committee headquarters in the Watergate complex in Washington, D.C., all the way back to Richard Nixon’s White House. Many investigative current affairs programs and fictional political dramas framed a “Deep Throat” in the sinister concrete gloom of a multi-storey car park in homage to the 1976 film All the President’s Men.

Few tyro journalists of the last 40 years have not fantasised about posing the famous Watergate question in the US Senate:

What did [fill in the accused] know and when did they know it?

Scandals involving politicians (as well as sportspeople and others) routinely attract the suffix “-gate”.

“Gate” has often been attached to an object, deceptively innocent in its connotations, that only serves to highlight the egregious nature of corruption and deceit. Sometimes “affair” works better, as was the case with the 1982 colour TV affair involving Fraser government ministers Michael MacKellar and John Moore and the alliterative 1984 Paddington Bear affair concerning Hawke government minister Mick Young. All three men lost their ministerial positions in these “affairs”.

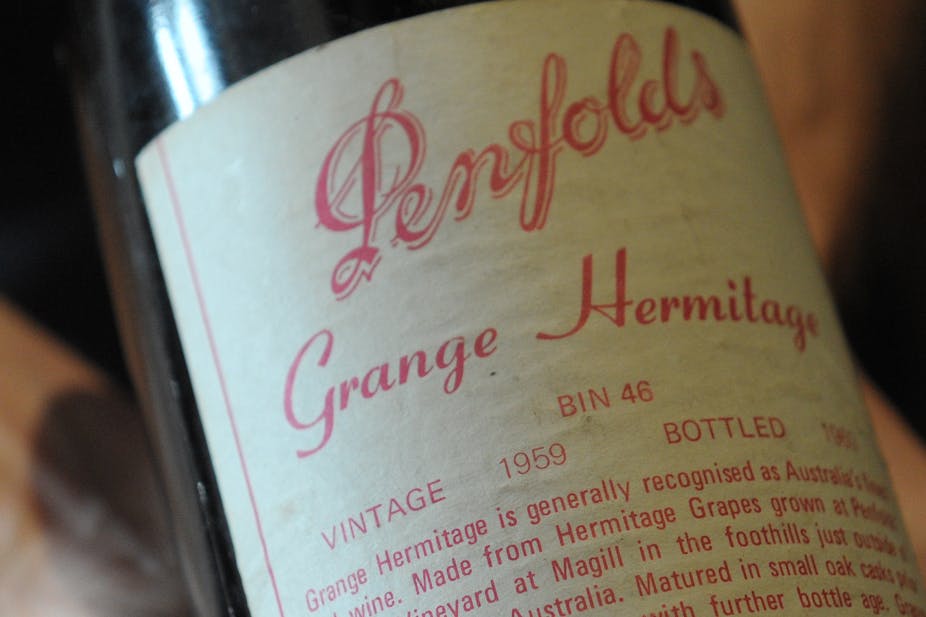

All this is essential cultural background to interpreting “Grangegate”, the boilerplate description of the sudden resignation of New South Wales premier Barry O’Farrell last week over the unacknowledged receipt of a A$3000 bottle of Penfolds 1959 Bin 46 Grange Hermitage from a lobbyist. Divining the significance of the wine has somehow become entwined with the political ramifications of the scandal itself.

There is an obvious – if rather worrying – reason for this heavy focus on the expensively fermented grape. There have been so many high-profile political scandals it is hard to keep track. Many people – not least those in a news media dedicated to the quick, relentless turnover of news stories – have resorted to mnemonic triggers to aid recall and to distinguish one scandal from another.

Forging collective cultural memory while being deluged by information relies on highlighting a single detail to symbolise the whole sorry business of political exposure. In communication theory this is known as metonymy – the use of a part to signify the whole.

In O'Farrell’s case, ritzy red wine stands for political influence-peddling and duchessing.

Many people, though, will never grasp the whole because they have not followed the story closely. And with the passage of time, many more will know next to nothing about it. But the metonym – which in the digital world has mutated into the meme – can live on, another of the “gate” and “affair” curios to be interrogated and mocked.

What, then, is the meaning of the “Grange” in “Grangegate”? Only recently on his trade trip to Asia, prime minister Tony Abbott was recommending Penfolds wines to Chinese president Xi Jinping. Grange has become a byword for New World vinous opulence, both as a present exchanged among the affluent and as a commodity traded on the international premium wine market.

Bottled wine is widely seen as a sophisticated commodity and its appreciation a marker of a cultured palate. For Shakespeare’s Iago in Othello:

Good wine is a good familiar creature, if it be well used.

But as a contemporary luxury good, its ill-use can – as O’Farrell painfully discovered – have dire consequences.

That the wine is red provides additional piquancy. In his essay Wine and Milk in the classic 1957 work Mythologies, French cultural theorist Roland Barthes argues that wine:

In its red form, [it] has blood, that dense and vital fluid.

In NSW, it has drawn unexpected political blood before the Independent Commission Against Corruption.

Grangegate now takes its place among the litany of political “gates” and “affairs” in Australia connected to banal everyday objects, among which can be counted 1994’s “Sandwichgate” involving Keating government minister Alan Griffiths.

More recently, 2009’s “Utegate” involving Kevin Rudd had a memorably folksy ring. That this sturdy workhorse vehicle, beloved by tradies, might be implicated in a political scandal caused some consternation in the ranks of Australia’s petit bourgeoisie. However, the ute in question in the end only dented the duco of then-opposition leader Malcolm Turnbull.

My intention here is not to trivialise the issue of political scandal, actual or alleged. Public probity and its policing is no laughing matter. But among the welter of allegations, denials, revelations and confessions across multiple institutional and social media platforms, the citizenry-at-large has considerable difficulty in discerning and – ironically in terms of O’Farrell’s woes – remembering what really matters.

Often, recall is reduced to a bizarre-sounding “gate” or “affair” rendered absurd by its association with the likes of a foodstuff, vehicle, soft toy, white good or beverage. In echoing the Porter in Macbeth, imbibing fortified media scandals and their catchy titles:

…provokes the desire, but [it] takes away the performance.

Here, it detracts from understanding and analysing our political environment. Another bottle of red is not the antidote.