Did you know the clitoris is a large and complex organ? If not, it’s probably not your fault: in anatomical textbooks, few words and diagrams are devoted to understanding the clitoris. Most label the very small portion of the organ visible on diagrams of the vulva, when in fact it’s almost entirely under the skin.

Studies of historical anatomical textbooks have shown that depictions of the clitoris were significantly limited and often omitted completely from the mid-19th into the 20th century.

During these times there were ideologies and subsequent theories relating to women’s bodies that likely encouraged and sustained censorship of the clitoris. For instance, there was Freud’s now defunct theory that clitoral stimulation was a sign of sexual immaturity and neurosis. Women were also taught not to enjoy sex; women had sex for reproductive purposes, while men had sex for pleasure.

These fallacies led to the neglect of the clitoris in research, literature and the public domain.

Although more recent research and feminist lobbying have improved the quality of information on the clitoris in current textbooks, most texts are still brief. These include minimal information, or information only on the external portion of the clitoris (the glans). This brevity has impacts on health care for women with clitoral and related pain.

What is the clitoris?

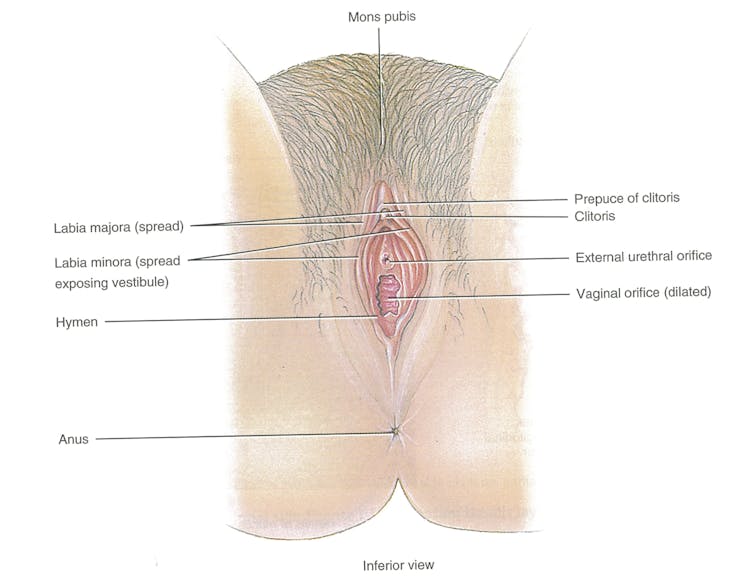

The clitoris lies at the junction of the labia minora (the inner lips of the vulva), just above the urethra. It is made up of four main parts: the glans, body, two crura and two bulbs. The glans is the only external part of the clitoris and is covered by a hood of skin.

The body, corpora, crura and bulbs of the clitoris are all made up of erectile tissue and converge below the glans. The body of the clitoris is generally 1-2cm wide and 2-4cm long.

The crura extend laterally from the body of the clitoris and are on average around 5-9cm long. The bulbs of the clitoris are generally 3-7cm long and lie between the body, crura and the urethra.

The clitoris is highly innervated, with twice as many nerve endings as the penis, and receives a rich blood supply. This rich blood supply allows the erectile components to swell up, with the body and glans of the clitoris becoming up to three times larger during arousal – and you thought a penile erection was impressive!

Foetus genital and reproductive organs are differentiated at six weeks’ gestation. While the clitoris and penis arise from the same group of cells in a zygote, we now know they clearly have different forms and functions.

The penis has an obvious and well-researched role in the reproductive and urinary systems, while the function of the clitoris is usually stated as being purely for pleasure.

However, few studies have actually investigated the function of the clitoris. The close proximity of the clitoris to the urethra and vagina has led to suggestions that it plays a much larger role than sexual pleasure, such as assisting in maintaining immune health.

What we don’t know can hurt us

Censoring the clitoris in textbooks means doctors and other health-care professionals won’t be equipped to treat patients with clitoral concerns. Women are at risk of sexual dysfunction (such as lack of desire or arousal, decreased lubrication, inability to orgasm) from operations on their urinary and reproductive organs. This shows doctors need more in-depth knowledge, and we need further research into understanding the anatomy of the clitoris.

Because of its delicate yet complex make-up, the clitoris is prone to infections, inflammation and diseases. Some common examples are itching and soreness due to thrush infections, swelling due to bruising or inflammation, and pain of unknown origin (called clitorodynia).

Although it is not often spoken about, clitoral and vulvar pain are very common in women.

Educating patients about their condition can improve pain outcomes. Yet this may be difficult for doctors treating conditions such as clitorodynia, given they may not be receiving adequate information about the clitoris themselves.

On average, one-third of university-aged women are unable to find the clitoris on a diagram. We frequently use synonyms of females’ reproductive organs as derogatory terms (“pussy” to mean weak, “cunt” to mean an unpleasant person) and many women are often not comfortable using anatomically correct terms.

More than 65% of women say they feel uneasy using the terms vagina and vulva. Instead they use code names such as “lady parts”, even when discussing gynaecological issues with their doctors.

Given there is evidence to suggest our sense of body ownership can influence pain, perhaps this lack of body ownership over the clitoris helps to explain why conditions such as clitorodynia are common.