A quick look at the winter transfers specialised websites as the mercato opens will immediately remind you that football players are mere commodities, just like any other goods put up for auction. Yet the men who will be “bought” this winter are just the tip of the iceberg. Many others will never even get there. But, nevertheless their lives have been dramatically affected. Like, let’s say, Michael.

A young man from West Africa, Michael was determined to make it as a professional soccer football player, like so many other young men throughout the region.

For this to happen, however, he had to land a contract with a club in Europe. And so, along with two friends, he enrolled the services of a local sports agent, who promised the group a trial in a country in the former Yugoslavia. But first they had to travel to Cairo, where the country’s nearest consulate is located, to apply for a visa. As they were waiting for their visas, their money ran out, so they had to depend on the generosity of West African migrants they had met while playing casual games of football around the city.

The consulate finally issued Michael a tourist visa, valid for 11 days. He travelled to the capital of the country in question where, unsurprisingly, the trial did not result in a contract offer.

His visa about to expire, he moved to a neighbouring country with more benign immigration laws than other European countries, and applied for refugee status. He was taken to a centre for prospective refugees, which he was allowed to leave in the daytime. Michael soon met a local woman and got married, which qualified him for residence status, and he was recruited into a third-league football club. He still dreams of making it to a premier league in one of Europe’s major football countries, such as Spain or Britain, as he struggles balancing training with low-end daytime jobs to make ends meet. (Details of the story have been altered to preserve anonymity.)

Michael’s story, which co-author Niko Besnier along with Susan Brownell and Tom Carter tell in their recently published book, reflect our research over the last five years and lives of young men who get trapped and submit themselves to various forms of domination, whether in soccer, rugby or other sports.

Why has professional sport become the lens through which so many young men in the Global South are redefining their future?

Sport as hope

To answer this question, we need to cast our analytic net over a broad sweep of social and economic transformations the world has experiences since the 1980s.

That decade saw the rise of neoliberalism throughout the world, and with it the liberalisation of trade. This has had the effect of rendering small-scale agricultural production unviable – commodity prices, now largely determined by speculators in the financial centres of the world, became too volatile. Many postcolonial states experienced significant economic downturns and had to turn to the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund and wealthy donor countries to avoid economic collapse. But loans came with conditions of austerity measures, such as the reduction of the civil service, which in many countries was the primary source of middle-class waged work. Whether educated and not, young people were now left high and dry.

At the same time, in wealthy countries, the same period saw sport become a cutthroat business. In Europe and elsewhere, the impetus was the privatisation of television channels in the 1980s, which drove up the price that networks were willing to pay for broadcasting rights. Another was the transformation of many clubs and teams into corporations competing for players, television coverage and financial backing, encouraging scouts to look further and further afield for “raw talent”. Yet another was the emergence of satellite television, which for the first time brought images of sporting glory and economic success to the remotest corners of the world.

It is at the convergence of these global transformations that we need to understand why in so many locations young men, no longer able to find decent employment in their home countries and fed on the images of sporting glory they watch on satellite television, invest their hopes for the future in dreams of sporting success.

Ending up in the backwaters of the sport world

In our October 2018 ethnographic comparative study of rugby in Fiji, football in Cameroon and wrestling in Senegal, we found that the lives of young men and their hopes for the future has been transformed by the world of sport strikingly in strikingly similar ways in very different locations. In some cases, such as Pacific Island nations like Tonga, the state itself encourages its young sport talents to migrate, policies that kill two birds at once: they are an easy solution to the labour crisis and they potentially generate valuable remittances from sport migrants who have made it.

Yet the possibility of a successful career in professional sport pales in contrast to its probability. As Michael’s story illustrates, young aspiring sportsmen are much more likely to end up in the backwaters of the sport world, such as Eastern Europe or Southeast Asia, than pursuing their dream career and supporting families back home – or worse, such as drowning while crossing the Mediterranean trying to reach countries that are increasingly hostile to economic and other refugees.

When religion walks in

In a context where the present has so little to offer and the future is, more than ever, an unknown country, another piece of the puzzle emerges: religious faith. As is well documented, certain forms of religiosity like charismatic Christianity and Pentecostalism are spreading in the Global South, and young sport hopefuls are flocking to these denominations.

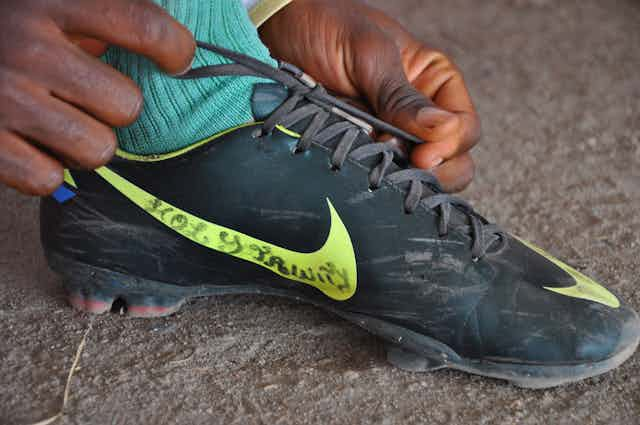

In Fiji, for example, young indigenous Fijian men in towns and villages today assiduously take part in daily rugby training sessions in hope that both their determination and their faith in God will bear fruit: they pray before and after training, inscribe Bible verses on playing boots, and sing hymns after listening to the club pastor’s post-training sermon. “I have to trust in God’s plan for me”, one of Daniel Guinness’s teammates explained, “I know that anything is possible through Him”. Then, paraphrasing Galatians 6:9, he explained that he was “preparing the field” in order to be ready for God to produce “a harvest of blessings” in his life.

The similarities we find in such diverse locations as Fiji, Cameroon, Brazil and, with Muslim ingredients, Senegal are striking. In religious faiths like Pentecostalism, success hinges on a predetermined talent and purpose that can only be realised through constant work.

Time-consuming and exhausting training regimes become an individual moral imperative to serve a God who determines one’s future. Charismatic faiths give the young sport hopeful a sense of hope in the context of a profoundly unsatisfying present and a deeply uncertain future. Sport federations and international governing bodies, too preoccupied with their own money-generating pursuits, have yet to wake up to the effects these dynamics have on youth in the Global South.

A source of hope can come from migrant players themselves, following the lead of Pacific Island rugby players in Europe, who have organised to deal with some of the most egregious problems they face.