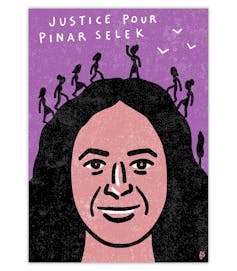

On 31 March 2023, a trial will be held in Istanbul against Pinar Selek, a sociologist, writer, feminist, anti-militarist and pacifist activist, exiled in France since the end of 2011 and facing life imprisonment in Turkey.

Selek has suffered from relentless judicial persecution by the Turkish authorities for 25 years – half a life. The reason? Her refusal to reveal the identity of the people she interviewed during an investigation she conducted on the Kurdish movements.

Arrested in July 1998, she was tortured and imprisoned for more than two years. Behind bars, she learns she is accused of having planted a bomb that would have exploded in the spice market in Istanbul, killing 7 people and injuring 121.

Selek was released at the end of December 2000, and acquitted in 2006, 2008, 2011 and 2014 following expert reports showing the tragedy was caused by the accidental explosion of a gas cylinder. Although the Turkish judiciary has cleared her four times, the prosecutor has appealed after each acquittal. After a silence of almost nine years, the Turkish Supreme Court announced the annulment of her latest acquittal and thus this new trial, which will be held in her absence.

Even before the 31 March hearing, Pinar Selek was the subject of an international arrest warrant by Turkey. Nine years after the researcher’s last acquittal, it is difficult not to link the Turkish justice’s revived interest in the academic to the forthcoming presidential and legislative elections scheduled for May and the celebration of the centenary of the Turkish Republic.

Beyond Pinar Selek’s personal plight, this episode illustrates the repression academics have faced in Turkey for years and which intensified further after the 2016 coup attempt.

Scientific freedom at risk

Wanted for “sociological crime”, the researcher has said, “I will not give up.”

Since arriving in France in 2011, Selek has defended a doctoral thesis in political science at the University of Strasbourg, published a myriad of scientific works and taught at the Université Côte d'Azur. After benefiting from a state grant for exiled artists and scientists for the first two years, she was awarded a permanent teaching-research position in 2022 by the University of Côte d'Azur.

In her plight, it is also academic freedom that is at stake. The presidents of the Côte d'Azur and Strasbourg universities, as well as numerous research laboratories and other university and scientific bodies have publicly taken a stance in her favour. University, student and activist support groups have also been formed. She was appointed honorary president of the Association of Sociologists of Higher Education. A delegation of nearly a hundred French and foreign representatives from the civil, associative, cultural, artistic, political, legal, scientific, academic and student worlds will travel to Istanbul to attend her trial, demand the truth and officially ask for justice to be done.

Engaged in a movement to open up the social sciences to society and to criticise scientific postures in the service of the established order, Pinar Selek is a “scientist in danger”. Even though she obtained French citizenship in 2017, she continues to suffer the political violence of an authoritarian regime that attacks the autonomy of the academic world – a phenomenon over which Turkey has no monopoly. Many Iraqi, Syrian, Afghan, Egyptian, Turkish, Iranian and other academics are paying a heavy price through state repression.

A situation that has escalated in Turkey since 2016

The situation of Pinar Selek reflects the rise of authoritarianism in Turkey, particularly noticeable since the strengthening of presidential powers following the April 2017 referendum.

Following the coup attempt on 15 July 2016 in which hundreds of civilians, soldiers, police officers lost their lives, a large number of academics have been designated as targets by the country’s president, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan. The signatories of the Academics for Peace Petition have been accused of terrorism, subjected to professional ostracism, prosecution and media lynching.

Among them, 549 academics have been forced to resign or retire, dismissed, revoked and banned from public service under the decree laws. The case of the “Gezi Seven” is emblematic of the massive repression of human rights in the country. Among them, publisher and patron Osman Kavala, imprisoned in 2017, was sentenced to life imprisonment for organising and financing the Gezi protests in 2013, without the possibility of parole after being unjustly convicted of an “attempted coup d'état”.

Although there was a Turkish Constitutional Court decision on 26 July 2019 acquitting them, these academics have lost their jobs and have been subjected to harassment in their professional environment. In addition, the Turkish National Research Agency blocks their publications. Terrorism charges continue, especially in relation to the Kurdish issue. For example, in October 2021, writer Meral Simsek was sentenced to one year, three months in prison for “propaganda for a terrorist organisation”.

Threats are also made to researchers based in France. In 2019, the mathematician Tuna Altinel, a teacher-researcher at the University of Lyon 1, who was accused of terrorist propaganda for having taken part in a public meeting in Villeurbanne on the army’s war crimes in the southeast of the country, was arrested in Turkey. Released after three months, he was only able to get his passport back and return to France in June 2021, after a long battle which is not over yet.

Hundreds of abusive arrests, acquittals – most often overturned on appeal by the Court of Cassation – and cases retried despite the recommendations of the European Court of Human Rights, punctuate this bleak picture. But the many hardships faced by researchers have strengthened their solidarity, as evidenced by their stories in Eylem Sen’s documentary Living in Truth.

In the name of the unconditional freedom of expression of researchers

“By condemning Pinar Selek, the Turkish government is attacking the independence of social science research,” reads the headline of

An article published in Le Monde in July 2022 by a group of academics, “By condemning Pinar Selek, the Turkish government is attacking the independence of social science research”, reminds us of the vulnerability of researchers to the attacks they face in many countries.

International conferences and declarations regularly reaffirm the protection of academic freedoms, but maintaining them requires constant struggles by the academic community and they are, in fact, never permanent students, professors and researchers are always at best suspected or threatened at worst arrested, tortured and killed, when strong powers are established to which they refuse to submit.

A “poetry activist”, as she likes to call herself, Pinar Selek, who is also the author of novels and children’s stories, is subject to political violence that can only be combated by denouncing and overturning her life sentence. Her tireless struggle against injustice, oppression and attacks on academic freedom, which are now being undermined in many parts of the world, illustrates that of all threatened scientists in authoritarian countries, but also in democracies.

Our solidarity with her is more than a moral duty. It is part of a shared struggle in the service of freedom of research and the exercise of a citizenship that must more than ever assert itself as transnational.