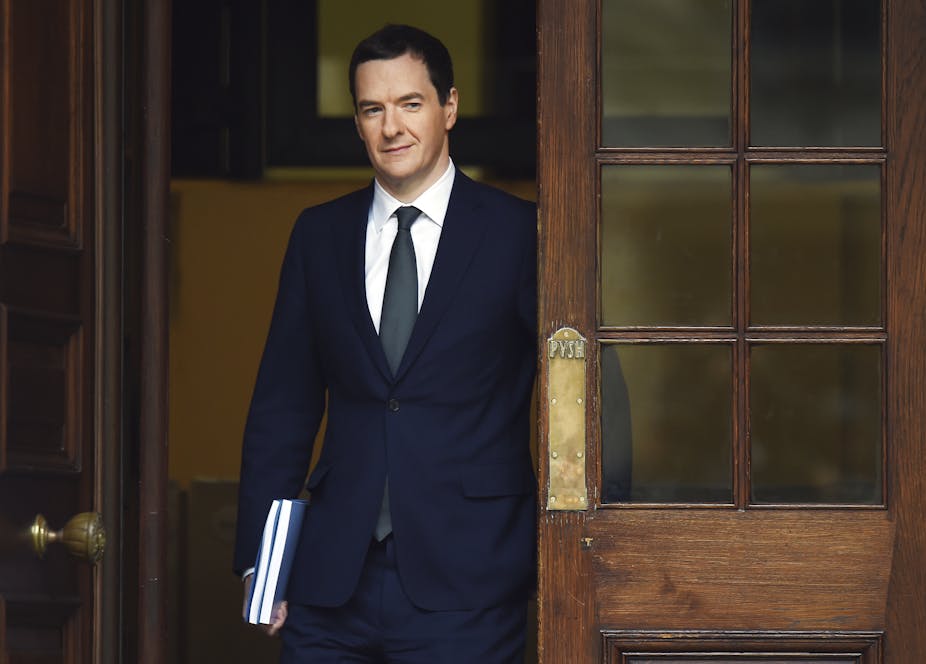

Chancellor George Osborne has set out government spending plans up to 2020. These involve big cuts to Whitehall and welfare, but also promises including a new phase of house building. Our experts from across the sectors give their thoughts on how the axe has fallen. For further updates on Twitter, follow @ConversationUK.

The Economy

Michael Kitson, lecturer in global macroeconomics, Cambridge Judge Business School

The Autumn Statement was infused with the predictable disingenuous rhetoric masquerading as responsible economics supported by a selective and obfuscating ragbag of numbers. George Osborne preaches about “economic security” and the need for a “strong economy." But the economy is weaker and less secure because of his policies.

As the IMF has shown, cuts in government spending weakens economies. The lesson from all competitive modern countries is that a strong economy requires a strong public sector: to produce the skills, the ideas and the infrastructure that fuel long-term prosperity.

Osborne talks about "rebuilding Britain” and says that the economy is “motoring ahead”, but he ignores that we have had the slowest economic recovery since the industrial revolution. The economy would have been more prosperous if he had buried his head in the sand and done absolutely nothing since being appointed in 2010.

Yes a country has to “live within its means”. But that is not reflected in the budget deficit, but in the the balance of payments deficit, which shows whether the country spends more than it earns. And the UK does spend more than it earns.

The balance of payments deficit (on current account) widened to £92.9 billion in 2014 (5.1% of GDP) and the largest annual deficit since records began in 1948. So the deficit that matters has been ignored.

There is no plan to ensure that the country will live within its means: no plan for exports; no plan for productivity; no “march of the makers”.

Gareth Downing, senior lecturer in economics, strategy and marketing, University of Huddersfield

Osborne’s estimates are based on maintaining growth in the 2-2.5% region and tax revenues increasing accordingly. While the latest figures from the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) raise tax receipt forecasts, recent growth figures have taught us to be wary. Meeting the proposed debt and deficit targets will also require continuing with large and as yet unspecified cuts.

The sluggish global economy, suffering from a lack of demand, is not helping. Plus, monetary policy, despite years of zero interest rates as well as unconventional measures such as quantitative easing, is unable to generate a strong recovery. In this environment, government cuts merely compound the demand problem.

The only way out of this nightmare is to aim for robust economic growth that raises incomes sufficiently to increase tax revenues. Even if this means accepting higher debts in the near term.

Alan Shipman, lecturer in economics, The Open University

The chancellor’s ability to scrap the £4.4 billion tax credit cut, add another £18.7 billion to public net borrowing from 2016-17 to 2020-21 and still deliver a £10.1 billion surplus in 2019-20, is entirely due to the “£27 billion improvement in the underlying forecast” provided by the OBR.

So, as well as the still-large departmental and social service cuts to come, more attention will turn in the next few years to how the OBR is conducting its forecasts, and particularly why it has raised its revenue forecasts when growth is slowing and the chances of an outright recession are rising. An unspecified boost comes from “modelling changes to our NIC and VAT deductions forecasts”. If the OBR gets its forecasts seriously wrong, in a way that unduly favours the Treasury (and brings nasty surprises later), its credibility as an independent assessor will be seriously affected. The art and science of macroeconomic forecasting are now as much on trial as the chancellor’s political skills.

Housing

Vikki McCall, lecturer in social policy and housing, University of Stirling

The spending review promises to unveil “the biggest affordable housebuilding programme since the 1970s with a particular focus on the creation of 400,000 "affordable homes” by 2020. As a useful comparison, research in Scotland indicates the need for a minimum of 12,000 of these over the next five years.

But there is a question mark around what “affordable” actually means and if this will be of any use to those with the greatest housing need. Affordable housing in the Scottish report, for example, was categorised as:

A broader category of housing tenures that includes social housing, but also a plethora of low-cost homeownership and mid-market rent schemes.

The focus of the spending review, however, is very much on home ownership. For example, the housing budget is being doubled to £2 billion, the Help to Buy shared ownership scheme is being extended and tenants of five housing associations will be able to exercise their right to buy.

A focus on low-cost homeownership has been shown to be problematic. And neglecting to invest in much needed social housing and changing how housing benefit is calculated by capping it at LHA rates will contribute to further pressure being put on existing, insufficient stock and tenants. This will, in turn, lead to further inequality throughout the UK.

Health

Karen Bloor, professor of health economics and policy, University of York

This year’s NHS funding settlement was more hotly anticipated than ever. The bottom line increase for NHS England – £3.8 billion above inflation for 2016-17 – sounds generous compared with other areas of government. Ring-fencing clinical care and “front-loading” a promised £8 billion might just keep the NHS on the rails.

Or maybe not. Hospitals anticipate £2.2 billion in deficits this year. And a seven-day NHS will cost hospitals £1 billion-£1.5 billion a year, plus the same again for primary care. Together, these costs could soak up the new funds.

Public health and social care budgets are not protected, limiting capacity to prevent illness and care for vulnerable people outside hospitals. And 2% increases in council tax for social care will not make up for annual reductions of 2.2% since 2009, which hit deprived areas hardest. Partly as a consequence, delayed discharges from NHS hospitals are at their highest levels since 2007.

Since 2010, the NHS has faced unprecedented spending constraints – an average annual budget increase of just 0.84%: a quarter of the overall average since the 1950s. Even with this settlement, the NHS must continue to increase productivity at a higher rate than it has managed throughout its history.

Welfare

Susan Harkness, reader in social policy, University of Bath

The reversal of the decision to cut tax credits provides welcome relief to the 3.3m families who would have been £1,300 a year worse off next April. Yet, while the announcement is to be welcomed, the longer term outlook for low and middle income families remains worrying.

The reversal does not extend to the new system of Universal Credit (UC), which by 2018 will have replaced tax credits for most. And cuts to UC have not attracted the same level of opposition. As Patrick Wintour tweeted, these cuts were approved last week with just 12 MPs present.

Other measures will, supposedly, compensate for these losses. The living wage and tax cuts will, it is claimed, help families as the UK moves from what the chancellor describes as a low wage, high welfare economy to one where all earn a decent wage. The living wage, as Ruth Lister has highlighted, cannot take account of family responsibilities, however. Only the tax and benefit system can do this.

Yet the current government sees children as being the responsibility of parents – and from next year those who have a third child will not be entitled to additional benefits for that child. The state is increasingly withdrawing from supporting and taking responsibility for families with children. Today’s measures stall this process, but the longer term trajectory for low and middle income working families remains unchanged.

Education

Roger King, visiting professor, University of Bath

With the 17% cut to the Department for Business, Innovation and Skills budget lower than feared thanks to a more optimistic economic outlook, higher education does not appear to have been badly treated in the spending review.

Science spending will continue to be protected – but this time in real, and not simply cash terms, as it was under the coalition. Partly in return, there are likely to be savings made by reorganising the research councils under one body – Research UK – with Osborne indicating he will accept the recommendations made in the recent review by Paul Nurse, president of the Royal Society.

The second development concerns student finance and the inexorable rise of loans rather than grants for students of all kinds. Student nurses will now be funded by loans rather than grants, so allowing a considerable increase in the numbers being trained and available for the NHS. Most welcome is the announcement that virtually all postgraduates will be eligible for the new student loan scheme, rather than just those under aged 30 as was initially proposed.

Perhaps most significant of all is that part-time students will also be eligible for maintenance loans. Part-time numbers have been in desperate decline recently despite access to tuition fee loan funding – this should help to reverse trends.

In the small print, the government also announced it would press ahead with the sale of the pre-2012 student loan book with a first sale expected in 2016-17.

Anna Vignoles, professor of education, University of Cambridge

It could have been worse for schools. The government has committed to protect school funding in real terms and to maintain the rate of the pupil premium for disadvantaged students. And these commitments come with some protection of funding for 16 to 19-year-olds too.

As part of the government’s goal of abolishing the role of local authorities in the school system, sixth-form colleges can now also become academies and get a financial incentive to do so (they won’t have to pay VAT).

All this perhaps offers some financial reassurance to the sector. But, and this is a big but, there is still hardship ahead for schools. The most significant change in the long run is to the way schools are funded, with the development of a new national school funding formula.

The aim of the new formula is to reduce differences in funding across schools. This will certainly cause big pain for some schools as their budgets are adjusted from 2017. The speed of adjustment to the national formula will determine how bad that pain will be, though clearly it would have been far worse if the overall schools budget had also been cut.

Policing

Sharon Gander, lecturer in policing, Nottingham Trent University

Police forces around the country will be sighing in relief, after the surprise announcement that there will be no real-term cuts to police budgets in England and Wales. In fact, spending is set to rise by £900m by 2020.

Police forces will, of course, be expected to make efficiency savings by sharing resources, something that has been shown to work effectively in the past. For example, earlier this year Warwickshire and West Mercia Police began sharing IT and training resources – and even responding to calls in each other’s localities – with great success.

Osborne has said that revisions to OBR forecasts have allowed him to spare some of the departments which seemed set for vigorous cuts. But the recent events in Paris, and stark warnings from senior police officers may well have been playing on his mind.

Pensions

Jonquil Lowe, lecturer in personal finance, The Open University

Pensioners in Osborne’s plans with a £3.35 a week increase in the basic state pension to £119.30 from next April. This is a 2.9% rise in line with average earnings, which have risen by more than price inflation or the 2.5% minimum promised under the “triple lock”. The new flat-rate state pension from April 2016 has been set at £155.65 a week. So pensions is one of the few (and largest) sections of the welfare budget to be protected.

The government is also set to promote a secondary annuity market which will allow people already drawing a pension to sell their income in exchange for a cash lump sum. Although this freedom may appeal to some, it is fraught with problems such as the risk of running out of money later in retirement. We’ll have to wait until December for further details.

As expected, the government has deferred any announcement on reforms to the way tax relief on pension savings is given until the March 2016 budget.

Scotland

David Bell, professor of economics, University of Stirling

The Scottish government now knows what is will be able to spend up to 2020. Its budget will increase from £25.9 billion now to £26.5 billion in 2019-20. This small increase in money terms translates into a 5% real cut, resulting from the application of the much reviled Barnett formula. The formula partly protects the Scottish budget, because a large proportion of Scotland’s spending is on health. In England, health spending will grow by 3.3% over this parliament and Scotland’s budget benefits from the “Barnet consequentials” of this increase.

On the other hand, since Scotland also spends a considerable amount on transport, the overall cut of 37% to the English transport budget will tend to pull Scotland’s budget down. Overall, the 5% cut in spending in Scotland is in line with that in Northern Ireland and slightly above the 4.5% reduction in Wales.

This spending review will challenge the Scottish government to make good the loss in real terms government spending. It could do this by increasing the Scottish rate of income tax. Scottish finance secretary John Swinney will announce this rate when he sets the Scottish budget for 2016-17 next month. His decision will be awaited with interest.

Business

Nigel Driffield, professor in strategy and international business, University of Warwick

Osborne has confirmed that the uniform business rate is to be abolished, and that local councils across England and Wales will have the right to set their own rates. In effect, it will be up to councils to determine their own optimum tax rates. This will involve a trade off between the number of businesses attracted by lower rates, and the reduced revenues that lower rates will yield.

This will inevitably create a degree of competition between councils. But in practice, this will mean that better off councils – or those that can move the burden of lower business rates onto households or cut services – will attract businesses away from less well off ones.

A levy on apprenticeships has also been introduced, leaving the UK’s biggest businesses with a £3m wage bill. While the headlines will focus on this cost to larger businesses, this is, in effect, asking them to contribute to training in the more vulnerable parts of their supply chains, which will be good for the economy in the long run.

Environment and energy

Steffen Böhm, professor in management and sustainability, University of Essex

Today’s spending review has hit the Department of Energy & Climate Change (DECC) hard. It’s budget will fall by 22%, probably resulting in job cuts, rumoured since the summer.

Support has already been cut for a range of green policies, including onshore wind, solar power and green homes. Now, we’re told that the Renewable Heat Incentive will go the same way – watered down “to save £700m”.

Support for home energy efficiency will also be significantly scaled back. Although Osborne claims that this “will save an average of £30 a year from the energy bills of 24 million households”, the vast potential for further energy efficiency measures will be left unrealised. In fact, he’s removing the incentive for energy intensive industries to become more energy and carbon efficient, by exempting steel and chemicals from the cost of environmental tariffs.

DECC never had much room for manoeuvre. The vast majority of its budget is eaten up by the nation’s dirty nuclear and coal legacies, leaving little money for transforming the UK’s energy system. And guarantees Osborne has given to Chinese and French energy firms for expensive nuclear and gas energy were conveniently omitted from the spending review.

In the lead up to next week’s climate change summit in Paris, Osborne’s policies will make it extremely hard for the UK to stick to its carbon reduction and renewable energy commitments.