Articles on Garment workers

Displaying 1 - 20 of 22 articles

Garment workers around the world experience unacceptable forms of exploitation.

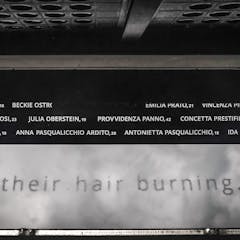

A memorial at the site of the 1911 fire remembers those who died; a cadre of young Jewish women helped push for change in the wake of the tragedy.

A new study suggests disclosure laws to prevent forced labour in the clothing industry are a form of window dressing designed to ease the conscience of consumers rather than protecting workers.

The collapse of Rana Plaza on March 24, 2013, put the focus on fast fashion. But research shows that stressed and struggling consumers don’t have the luxury of making ethical choices.

Producer responsibility is increasingly being used to deal with the environmental costs of production. It can also be used to deal with social issues.

Our new research sets out six ways to cut a more gender-just and sustainable fashion sector.

How could a company highly regarded for its commitment to sustainability do so badly on the industrial relations front, pushing staff to strike for almost a fortnight?

The US-Africa trade pact has had a significant impact on stimulating export trade – but African countries have not realised its full potential.

Fast fashion is far from green. But the rapid expansion of online clothing resale platforms could help shrink the garment industry’s negative impact on the environment.

Coronavirus has revealed the extreme plight of Bangladeshi factory workers.

Coronavirus has shifted the mood in society, and the fashion industry should strike while the iron is hot.

Fashion Revolution week puts a spotlight on the modern slavery conditions of the fashion industry and encourages fashion consumers to ask, “who made my clothes.”

Striking 20th-century garment workers wore their best dresses and hats to send a message that they had the right to be taken seriously and have their voices heard.

We wear the evidence of extreme inequality – clothing made by workers in Bangladesh for 35 cents an hour. But we know how to reduce inequality – we just have to do it.

Family day care workers have much in common with home-based workers in the garment industry. But the latter are classed as employees, resulting in better representation and protected work conditions.

Businesses can play a major role in either facilitating modern slavery or eradicating it.

Adding 20 cents to the price of a T-shirt in Australia would be enough to lift all Indian workers in the garment supply chain out of poverty.

Factories that produce fast fashion garments are still highly dangerous workplaces – and not just because they might collapse.

While the fashion industry may want to address worker exploitation in their supply chains, it would open them up to tremendous legal liability. This needs to change.

The Rana Plaza anniversary is a reminder of the transparency lacking in the garment supply chain for the clothes we wear.