Artikel-artikel mengenai Misinformation

Menampilkan 81 - 100 dari 356 artikel

In a world of increasingly convincing AI-generated text, photos and videos, it’s more important than ever to be able to distinguish authentic media from fakes and imitations. The challenge is how.

AI tools are now generating content that’s difficult to distinguish from reality.

We often assume misinformation leads to bad beliefs which lead to antisocial behaviour. But there’s so far little evidence for this.

You’d be surprised how far back the roots of anti-vaccine arguments stretch.

A philosopher unpacks the ‘ethics of belief’ for an age awash in bad information.

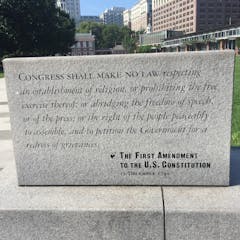

‘Congress shall make no law … abridging the freedom of speech.’ It’s often misunderstood, by many Americans. A constitutional scholar explains what it really boils down to.

Lateral reading, self-nudging and a persistent refusal to feed the trolls are some of the ways one can better manage information.

The amount of content available online makes policing misinformation extremely difficult. But there are steps we can all take to better ensure the credibility of what we see online.

Antisemitism often appears and spreads on social media. But digital technology can be part of the solution, too.

A university course teaches students why people believe false and evidence-starved claims, to show them how to determine what’s accurate and real and what’s neither.

Teaching students about information literacy can help them determine what kinds of practices make news reports trustworthy.

Suspended MP Andrew Bridgen’s comments are a prime example.

Conservatives have a long history of contorting the words of Martin Luther King Jr. to further political goals at odds with King’s vision of a colorblind society.

A key piece of federal law, Section 230, has been credited with fostering the internet and allowing misinformation and hate speech to flourish. Here’s how it could be reformed.

The intersection of content management, misinformation, aggregated data about human behavior and crowdsourcing shows how fragile Twitter is and what would be lost with the platform’s demise.

The key to understanding online conspiracy theorists is to understand how the line between fantasy and reality can become blurred.

For the first time, we are asking readers if they can help support our mission to share knowledge in order to inform decisions.

Fuel for the American Revolution came from a source familiar today: distorted news reports used to drum up enthusiasm for overthrowing an illegitimate government.

A wealth of research on social media shows that COVID-19 misinformation is damaging to public health.

For one, washing your hands is unlikely to prevent COVID spread.