Articles on Health inequity

Displaying 1 - 20 of 51 articles

Many Black patients experience stark differences in how they’re treated during medical interactions compared to white patients.

Research partnerships with the people and communities affected help to challenge health inequities, and support person-centred care in health systems.

Anti-Black racism has health, social and economic consequences for Black populations in Canada. Partnering with Black communities is a crucial component in effective efforts to mitigate inequities.

While medical school may teach students about how the body works, it often neglects the social, political and cultural factors that determine health and disease. The humanities can help.

The work environment is a social determinant of health. However, work has been underused as a lever to address health inequalities.

Cancer screening and other routine primary care can help address inequities if we choose to leave the unfair status quo behind.

Many people with sickle cell disease don’t receive adequate treatment to ease their pain and are subjected to racial discrimination and stigmatization.

Children as young as ten don’t have access to Medicare if detained. And they’re dying of largely preventable diseases.

Native Americans sent to government-funded schools now experience significantly higher rates of mental and physical health problems than those who did not.

The argument that private healthcare relieves pressure on the public system is misleading. Private care profits from failures of the public system and patients’ desperation for timely treatment.

Biased algorithms in health care can lead to inaccurate diagnoses and delayed treatment. Deciding which variables to include to achieve fair health outcomes depends on how you approach fairness.

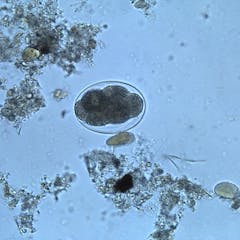

Though many Americans believe that parasitic infections exist in poorer countries, research shows that the problem exists in the US and has a higher impact in communities of color.

As negotiations for an international pandemic treaty get underway, public engagement is in the best interests of Canadians. Here is how the federal government is consulting affected populations.

The Albanese government has promised a centre for disease control. Its main focus has to be health equity for disadvantaged groups.

The US PEPFAR initiative has brought HIV medication to millions of people globally. Behind this progress are the activists that pressured politicians and companies to put patients over patents.

Prejudice and stigma can discourage the communities most affected by infectious diseases from seeking care. Inclusive public health messaging can prevent misinformation and guide the most vulnerable.

Systemic social issues affect vaccine access and acceptability. Yet, the term ‘vaccine hesitancy’ overlooks this, reducing the multiple factors that affect vaccine uptake to individual-level choices.

Time is running out to expand an agreement to relax patent rules on COVID vaccines. Members of the World Trade Organization should broaden its scope to treatments and tests.

If we want people with complex care needs to prioritise their health, cutting patient fees, providing flexible hours and paying attention to their social circumstances would be a good start.

Children and youth in care are more likely to have experienced trauma that can affect future health. A comprehensive, trauma-informed health strategy for these children and youth is long overdue.